|

|

Chapter

3 The World War I Years  Major Hayes who was stationed at How Hill in WWI |

The Victorian way of life continued into the first years of the 20th century, but what brought about a change in Ludham and elsewhere across the country was the start of World War I. The army was not large at that time; numbering about 247,432 at the start of the war but by 1918 there were some five million people in the army and the newly formed Royal Air Force was about the same size as the pre-war army. Three million or so casualties of war were to be known as the "lost generation", and this without doubt left society scarred. The poems of Siegfried Sassoon were a blunt satirical angry protest about the war and young poets such as Wilfred Owen and Robert Graves also wrote about the reality of the evils of war. Conscription brought people of many different classes, and from all over the empire together and this mixing also accelerated social change after the war.

Social reforms from the previous century continued into the twentieth with the Labour Party being formed in 1900, but there was no major success achieved until the 1922 general election. Lloyd George said after the First World War that "the nation was now in a molten state” and his Housing Act 1919 would lead to affordable council housing which allowed people to move out of Victorian inner-city slums. The slums though, remained for several more years, with trams being electrified long before many houses. The Representation of the People Act 1918 gave women householders the right to vote, but it would not be until 1928 that equal suffrage was achieved.

|

The outbreak of the First World War was on 4th August 1914. Many young men volunteered in search of adventure, many assuming it would be a short war and that ‘everybody would be home by Christmas’. This would not have prevented them worrying whether their jobs would be available on their return home. Throughout history, Norfolk has been one of the counties most in line for invasion and attack from hostile foreigners and this was no exception in the sudden lead up to the First World War. Invasion was certainly feared as Norfolk was only eighty miles across the North Sea to the shores of an enemy nation. It was thought that our eastern coastal areas would give easy access for invading troops. Norfolk men and women were not afraid to stand up for their country. The memorial in St. Catherine’s churchyard in Ludham bears witness to the fact that Ludham lost eleven of its menfolk to the war. What is more difficult to calculate is how many actually signed up or were eventually conscripted and returned? Some may have been disfigured or mentally injured from the effects of the war. |

It is well known that across the country many young men lied about their age when enlisting. Older men over thirty, to start with, were unable to enlist and soon all over Norfolk a ‘Dads Army’ was formed with over six hundred in its ranks. Our army at the beginning of the war was a volunteer army. Signing up involved a medical for all recruits. This was performed, dare it be suggested, in a rather lax manner. Often the height and chest measurements, which were all that made up the medical, were adjusted to the required criteria. Advertisements, for recruits, were posted in towns and villages for the many different regiments often stating their requirements – being of a ‘good class’, ‘willing to serve abroad’ or ‘being a good horseman’. |

|

|

I think many of us may be aware of the ‘Kitchener Needs You’ poster. This poster was soon to be appearing in the Eastern Daily Press and encouraged, recruits signed up for three years or until the war ended. These recruits made up the Kitchener Army. |

By the end of August 1914 the age of enlistment was raised to thirty five or forty five for ex soldiers and up to fifty for NCOs. By 1915 The Military Service Act stated that all single men and childless widows aged eighteen to forty one were conscripted. However by 1916 a second act came in and ALL men eighteen to forty one were conscripted and in 1918 it was changed yet again so that all men up to fifty years of age were conscripted. This act had the power to extend again to any man up to fifty six years of age if it became necessary. Men were able to appeal but this was a difficult route to take with no guarantee of success. There were those who pleaded they were conscientious objectors – people whose conscience would not allow them to be in the army. These people could face jail sentences or just being handed over to the military anyway. There was a lot of public harassment against them. Those conscientious objectors that found themselves in the war and at the front were sometimes given non combatant duties and often performed exceptionally bravely helping with the welfare of the men, horses and equipment. Many may have gone out into the killing fields to bring back the wounded and dying. |

|

We must assume that many of the men recruited from the village left the Ludham farms short of workers, as was the case in many Norfolk areas. Norfolk being a good agricultural area could now not provide the much needed food for the people of Britain so wives, mothers and sisters were appealed to across Norfolk to take up work on the land sowing crops, hoeing, harvesting, milking and doing all the dairy work. It would not have been unusual to have seen female land workers in the fields around Ludham village during World War I.

As farm produce declined because of the shortage of working men on the farms and horses being commandeered by the army, along with the loss of foreign food coming in, household provisions started to become scarce. Rationing was not brought in until 1918 although some voluntary rationing had been tried prior to this date and food had been price controlled. People started to stockpile food which made matters worse so in 1918 ration books were introduced. Unfortunately, as happened in World War Two, a black market came about as unscrupulous people tried to take advantage. Special recipes appeared in the local press to help housewives make the most of their weekly allowance of foods and the Royal Horticultural Society issued advice on ‘how to supply your larder from your garden’. The residents of Ludham would have been used to doing this anyway, but for those in the large towns it would have been something new and challenging to do.

At this time much attention was drawn to the state of housing and the health of the nation. Often times of need and war pre-empt the introduction of medical breakthroughs, analysis of social standards and welfare and it is at this time that many men volunteering or being conscripted were found to be unfit for duty. The men of Eastern England were a little less healthy than the national average. This finding was based on their weight, height and chest measurements, not a full medical, but it alerted the authorities to the health and housing standards of the population and it also highlighted the poor health of children at this time. There were no benefit payments as such from 1914-1918 but wives were awarded a separation allowance. A wife would receive 12s 6d and if there were children it went up according to the number of children so a wife with four children would expect to get twenty-five shillings a week.

By 1917 the victims of the war were growing and so a new pension scheme evolved for ‘men broken in war’ as well as weekly allowances for widows and orphans.

Let us pay our respects not only to the men of Ludham named on our War Memorial but also to all those who enlisted from Ludham and its hamlets and did return. They are listed at the end of this chapter. Families left behind had very little comprehension of what their men would have been going through. The terrible conditions in the trenches in France and the savagery of war in other parts of the world would have been hard for families to imagine and servicemen to forget and some came back unable to work as before and may have felt themselves a burden rather than a blessing to their families. However, families were reunited with husbands, fathers, sons, uncles, cousins and life did go on, and one would hope that in a village like Ludham the fortunate were only too happy to give a caring hand to help the more unfortunate casualties of the war. The dead are revered and monuments erected in their memory as it should be and one can’t but be moved and saddened viewing the endless list of names on foreign memorials and on foreign commonwealth graves as well as on memorial plaques across the country but how did the returning men feel?

The ‘life’ they returned to was to be eventually embroiled in the depression and poverty of the 1930’s. Very soon into the war wounded soldiers started to arrive by the train load into Norwich. There were always crowds to meet the trains, greeting the soldiers with cheers and flag waving. At Thorpe hospital they dealt with 41,000 wounded in 322 convoys during the war. As the hospitals filled up, places like Hoveton Hall housed the wounded also.

Some practical help for ex-servicemen was at hand after World War I, for between 1920 and 1925 a government scheme provided work for these returned soldiers. North Norfolk District Council compulsorily purchased land from some of the bigger farms and set up 500 acres of smallholdings. There were at one time 11 smallholders in Ludham but as the depression crept in making a living from a smallholding became progressively difficult.

The first Poppy Day was held on 11th November 1921. Disabled ex-servicemen worked all year making poppies to raise funds for the benefit of widows, orphans and the 500,000 disabled British ex-servicemen. |

|

In Ludham we have the names of eleven men who fought and lost their lives in The Great War. As you, the reader will appreciate, it is getting harder as the years go on to follow up who these men were and what happened to them. With the help of relatives, the internet and luck we have some details of their war exploits and it is interesting to see that these men seemed to be in different regiments, in different parts of the world and met with death under different circumstances. Many of these fighting men changed regiment which does not always help when trying to trace them and of course many World War I records were lost in the 2nd World War. Two are remembered here in the graveyard in Ludham, others in Commonwealth Graveyards or named on a war memorial in a foreign land. Some however have been harder to trace and information remains unknown.

Leslie Thomas Bond:

Son of widowed mother Harriet living in Ludham, was 21 years of age and a Stoker 2nd class in the Royal Navy, assigned to HMS "Pembroke" Chatham. This was a barracks built to provide accommodation and training facilities for the men of the reserve fleet who were waiting to be appointed to ships.

| Before the war enlisted men had been

housed in hulks laid up in the River Medway. The

barracks, designed by Colonel Henry Pilkington, was

begun in 1897 (on the site of Chatham convict

prison) and the first phase of development (which

included the Drill Hall or ‘Drill Shed’ as it was

often called) was completed on 26th March 1902. The

second phase of building included the development of

barrack facilities such as swimming baths and a

bowling alley and was completed by December 1902.

‘H.M.S. Pembroke’ was adopted as the name of the

barracks as this had been the title of one of the

hulks which had originally housed the men. On 30th

April 1903 men entered the barracks by the main gate

for the first time to begin their occupation. The

barracks had cost £425,000 and could originally

accommodate 4,742 officers and ratings. The gates to

the Naval Barracks were finally closed on 31st March

1984. It is recorded that Leslie Bond Service No: K/32727 died on 26th May 1916 at HMS Pembroke of an illness. It has also been recorded that there were outbreaks of 'spotted fever’ epidemic (cerebro-spinal meningitis) in the barracks at certain times but there is no evidence to show whether this illness applied to Leslie Bond. Later in 1917 one of the worst atrocities of the war on the mainland occurred during a German night time raid when the glass roofed drill hall was bombed and the whole of the roof lifted and collapsed on the sleeping troops. This resulted in terrible injuries and a high death toll. |

|

Victor Alexander Brooks:

Son of Harold and Sarah Brooks of the Shrublands, now where Folly House, Ludham is situated, was killed on the 7th May 1917 at the age of 19 years. He was signed up with the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry 1st/4th Battalion - a battalion of the Territorial Force. On the 4th May 1917 the hired transport ‘Transylvania’ defensively armed, carrying troops from Marseilles to Alexandria was sunk by torpedo off Cape Vado a few kilometres south of Savona, Genoa Bay. The Times reported that 29 officers, 373 other ranks, the Captain, 1 officer and 9 of her crew were all lost. The Transylvania was escorted by 2 Japanese destroyers, the Matsu and the Sakaki. When the first torpedo hit, the Matsu closed in and started to take troops off but a second torpedo was fired and hit the Transylvania which then quickly sank. The soldiers, according to one survivor, were paraded five deep on deck when the first explosion occurred. There was a shout 'Women first' and the nurses, whilst they were being lowered into boats shouted out 'give us a song boys!’ The men responded with Tipperary and Take me home to Blighty. After the nurses were secured and just as a boatload of soldiers had been launched a second torpedo was fired. This caught the boatload of soldiers throwing them high into the air. The chief steward in the boat had a lucky escape but the others lost their lives. Excellent work was carried out by the destroyer which eventually had every available space on her decks covered with soldiers and nurses. Unfortunately for Victor Brooks of Ludham he may have met his death at sea and is one of those named on the Savona Memorial, Genoa, Italy as a casualty of the Transylvania sinking. One can also see a remembrance to him on a grave in St. Catherine’s graveyard Ludham. Ironically it may have been unfortunate for those surviving, as they probably would have gone onto the senseless massacre in Gallipoli.

Herbert W Clarke:

Some confusion has arisen as to his identity. Further research may give rise to conflicting evidence related to that which follows. On the 1901 census there is a 5 year old Herbert Clarke living at Norwich Road Ludham. This is the household of Winter, his father aged 54 years, a farm labourer and Elizabeth his mother aged 49 years. He appears to have a brother Charles aged 18 years at this time. On the 1911 census it shows Herbert still with his parents but living in Staithe Road Ludham. He is 15 and working as an assistant postman. Supposing that this is the correct person Herbert Wesley Clarke enlisted in Norwich and joined the Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment) 8th Battalion and could have been one of many marching with commitment in Norwich before proceeding to France and Flanders. He would have seen action as a corporal in the trenches, witnessing whizbangs, artillery and trench mortar activity and possibly gas shells. His grave is in the Trois Arbres Cemetry, Steenwerck. He was a private in the army and died, at the age of 22 years, on the 11 September 1918 just before the final battle of Ypres 28th September to 2nd October, 1918. He would no doubt have known what it was like to survive in the trenches, living from hand to mouth in muddy austere conditions awaiting orders. Did his older brother also go to war? He would have been about 31 years at the time and well within conscription age.

Ernest Gedge:

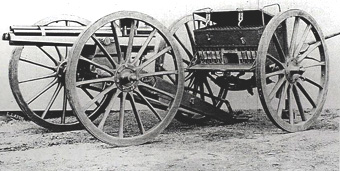

Born in Ludham, was thirteen years of age in 1911, living in School Road with his parents, Robert, a horseman and farm labourer on the Manships Farm and Ann his mother from Potter Heigham. He had an elder sister Blanche who helped at home and a brother Alfred, like him at school in Ludham. During the Great War, enlisting at Wroxham, he joined The Royal Garrison Artillery 11th Siege Battery as a gunner, Service No. 154061, serving in France. A siege battery was deployed behind the front line and had the task of destroying enemy artillery, supply routes, railways and stores. They were equipped with Howitzers and eighteen pound guns.

| An 18-pounder field gun had a crew of

ten, six of whom operated it in action. The gun was

drawn by a team of six horses with a driver on one

side of each pair. Each of the artillerymen on the

gun would have a number. No1 was in command (usually

a Sergeant). No2 operated the breech mechanism. No3

Limbers (part of a gun carriage) and unlimbers (with

No2) and fires the gun. No4 Limbers up and unlimbers

the ammunition wagon (with 5 and 6). No5 and 6 hook

in and unhook the ammunition team. No6 operates the

fuse indicator whilst No7 and 8 were the reserves at

the wagon line and assisted with ammunition and

replacing any casualties on the gun. No10 "Coverer"

took over in the event of an injury to number 1, but

looked after wagon teams in the mean time. |

|

The wagon team were always susceptible to attack, as the enemy targeted them because without ammunition and horses the gun pits efficiency was greatly affected. Ernest Gedge was killed in action and died on the 30th October 1917 and is laid to rest in Minty Farm Cemetery where there are 192 First World War burials, a third of these being officers and men of the Royal Artillery. From 1914 - 1919 49,076 Royal Artillery men met there deaths in the war.

Albert Leslie England:

Born in Ludham, 4th June 1892, the son of Kirby and Emma England. As an eight year old he lived on the High Street which on the 1901 census is shown as next door to The Stables on Butchers Street. This is the household of his parents, Kirby England aged 47, a butcher and farmer from Ludham and Emma his mother from Horning. There are other older children, Alethea, Alice and Kirby. At the age of 19 in 1911 Albert was single and boarding in Norwich, employed as a chauffeur but at 25 years of age and married to Fanny he enlisted on the 8th April 1916 into the Bedfordshire Regiment, subsequently transferring into the Essex Regiment 10th Battalion. Nineteen months later Signaller England died of his wounds on the 4th November 1917.

Being a signaller put you close to the frontline troops, providing communications back to Company and Battalion H.Q. Wired telephones were used where possible but this involved laying lines which was a hazardous job due to enemy shelling. Where it was not possible to lay landlines many forms of visual signalling were used which made use of the sun and mirrors in day time and lamps at night (Lucas Lamps). Messages were sent in Morse Code, one man operating the signalling device and one man using a telescope (where distances were great) to read the message being sent back. Signallers were also used in forward positions to assist the artillery and provide information on their enemy targets. In these positions, often isolated, the signaller became vulnerable to enemy shelling and attack, and many signallers lost their lives.

| The standard field telephone used

with landlines consisted of a wooden box containing

two dry cells, a magneto generator, polarised bell,

induction coil testing plug, and a "Hand Telephone C

Mk.1". Towards the end of 1916 these were replaced

by the Fullerphone and by 1918 many divisions

adopted them in their forward positions. |

|

Signaller England of Ludham village fought his battles in France and Flanders and is remembered in Etaples Military Cemetery. In 1917 100,000 troops were camped among the sand dunes and the many hospitals and convalescent depots which could deal with 22,000 wounded or sick soldiers. Perhaps this is where Albert England was taken on receiving his war wounds.

William Thomas Grapes:

At 23 he was living in a cottage on the Yarmouth Road in the household of his father, also William, aged 56, and a thatcher from Ludham and his mother Lucretia aged 53 from Potter Heigham. There were several younger sisters also recorded at the cottage. By 1911 he had moved to Johnson Street with his wife Sophia and was working as a bricklayer. He signed up, probably in Norwich, with the Norfolk Regiment 9th Battalion. The 9th (Service) Battalion was formed at Norwich in September 1914 as part of K3, Kitcheners Third Army. In September 1914 it was attached to the 71st Brigade, 24th Division. The Battalion was assembled around Shoreham during September 1914 and it then spent 11 months in training after formation. Uniforms, equipment and blankets were slow in arriving and they initially wore emergency blue uniforms and carried dummy weapons. The battalion crossed to France between 28th August and 4th September 1915 where they joined XI Corps and were sent up the line for the developing Battle of Loos.

They disembarked at Boulogne almost 1000 strong, but 8 days later they were reduced to 16 officers and 555 other ranks. The battalion lost a total of 1,019 men killed during the First World War. It marched from Montcarrel on the 21st September reaching Bethune on the 25th, before moving up to Lonely Tree Hill south of the La Basée Canal. They formed up for an attack in support of 11th Essex but were not engaged.

At 03:30 on 26th September orders were received to assist 2nd Brigade on an attack on quarries west of Hulluch. At 05:30 the Battalion were in what had, the day before, been the German front trenches. The attack was launched at 06:45 under heavy fire, especially from snipers, after a full night of marching on empty stomachs and little or no progress was made before the Norfolks sought cover in the trenches. At 16:00 2nd Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment passed through to attack. At 19:00 the Germans opened fire and the Norfolks were forced to fall back to trenches in the rear to take cover before being relieved by the Grenadier Guards whereupon they returned to Lonely Tree Hill. They had lost 5 officers killed and 9 wounded, with 39 other ranks killed, 122 wounded and 34 missing, a total of 209 casualties sustained in their first action. The 9th battalion took part in the battle of Loos on 26th September 1915. Private William Grapes at the age of 36 died on this date and he is on the memorial panel 30/31 Loos Memorial, France.

Corporal William Herbert Lemon:

Born in, and attended school in Ludham. On the 1911 census he is recorded as living with his widowed mother Ellen Mary and younger sister Emma Gladys in Ludham where he was working as a market garden labourer. In March 1915, at the age of 22, he enlisted in Norwich with the Norfolk Regiment but later transferred to the Border Regiment 7th Battalion. His regiment fought in the first phase of the Battle of the Somme as part of the 51st Brigade, 17th(Northern) Division, in XV Corps under General Horne, in the Fricourt- Becourt sector. On July 1st, they were in support, but on July 3rd they attacked and took Bottom Wood opposite Fricourt and were relieved overnight to Fricourt Wood. North East of Fricourt, attacks were made on Bottom Wood and Shelter Wood, the 17th Division capturing the former and 21st Division the latter. Counterattacks from Contalmaison were repulsed at 2pm. Corporal Lemon was killed in action on the 3rd July 1916 and he is remembered on the memorial panels in Thiepval Memorial.

Alfred Charles Moy:

Living in Johnson Street, Ludham in 1901 with his grandparents, Henry, a marshman from Ludham and Eliza his grandmother. Several of their children, namely Blanche, Cubitt and William were also at the residence. He was 4 years old and no evidence of his parentage at this time has yet come to light. At 14 he was still with his grandparents and working as an errand boy.

Alfred is one of the few on our memorial to join up with the Royal Navy and he was assigned to H.M.S. Adamant and entered service as a Stoker 1st Class. This ship looks to have seen service throughout WWI in the Mediterranean and used as a submarine depot ship. A note from a submariner captured by the Turks in the Dardanelles in early 1918 indicates that the Adamant was his depot ship. Alfred was 22 years of age when he met his death on the 5th June 1918: recorded as killed or died by means other than disease, accident or enemy action. He was however awarded the Star, Victory Medal and British War Medal. His grave is in the Civil Cemetery, Fiorenzulo Di Arda, Italy. His mother is recorded as Mrs Narborough of 17 Russell Street North Shields.

Percy James Phillippo:

He has a picture recorded on Norlink with the accompanying notes: Signaller Phillippo was born at Stoke Holy Cross on 27th October 1891, the son of James and Emma Phillippo of Ludham. He enlisted on 8th April 1916 in the 10th Bedford Regiment, but later transferred to the 10th Essex Regiment. The Genes Re-united transcription of the 1911 Census for England & Wales has a Percy James “Phillipps”, born Stoke Holy Cross circa 1892 and resident in the Smallburgh District. There is no “Phillippo”, “Philippo”, “Phillipo” or “Phillip” that matches for either the 1901 or 1911 census that matches any of the details known for “Percy”, “James” or his parents. He was killed on 12th August 1917. The 12th was a quiet day in the Battle of Passchendaele, after the initial flurry during the first week after the initial attack by the Allies on the 31st July. On the previous day the 18th Division, of which 10th Essex were part, had seen action in a small scale operation when the Germans attacked whilst the 8th Norfolks were relieving the 7th Bedfords in the front line. There is a reference to his death, killed in action, on Panel 39 Ypres (Menin Gate) Memorial. He is just one amongst the many at this most moving memorial site.

Arthur Webster:

We have no information about Arthur, but the 1911 census does have a Mary Ann Webster, born circa 1881 Ludham, and still resident in the Smallburgh area.

Many men returned to Ludham to live and die here, and some may have moved on to other areas of the country, or even the world where it was easier to make a living.

The horses never returned. Horses, whether they were heavy working horses on the farms or family ponies conscripted into the war, never came back and the village, once full of horses never returned to that state again.

A Century Of Change Had Begun In Earnest

| The Men Of

Ludham Who Went To War, And Returned! |

||

| George Henry Alexander Herbert John Beck William Beevor Reginald Ernest Bell Reginald Gordan Bensley Wilfred Henry Albert Blackburn Fredrick William Burton Issac Robert Burton Rev. George Alfred Braithwaite Boycott William Calver Reginald Chambers Charles William Clarke Charles William Cook Charles William Cooke Charles James Anguish Cooke Herbert James Cooke James Henry Cooke Bertie Benjamin Debage |

Edmund John Xxxxxx Alfred George Gedge Thomas William Gedge Albert Benjamin George Algernon Cecil George Frederick William Gibbs Richard William Gibbs Albert Arthur Grapes Herbert Alfred Gillings James George Gravenell Samuel William Hicks Francis William Jermy William Kemp Albert Wesley Knights Arthur Edwin Knights Thomas Charles Oscar Long Sidney John Frederick Marr Arthur Frederick Newton George Pollard |

Edgar William Phillippo Herbert William Reynolds Alfred William Riches John Herbert Sayer Robert James Shand Stanley Grapes Shand Aubrey Slaughter William Slaughter John Temple William George Temple Ebenezer Tillet William John Tillet George Frederick Thrower Thomas Arthur Thrower Jonathan Henry Thrower Robert Turner Frederick Varley Leslie William Watson |

Sources:

Norfolk in the First World War by Frank Meeres

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

Norlink