|

|

Chapter

2 Farming In The Twentieth Century

Ludham from the air (Photo: Mike Page) |

In Ludham as elsewhere, the twentieth century saw a transformation in the patterns of agriculture and rural life that had endured for centuries. Although agriculture continued to shape the appearance of the village, its importance as the major employer, both directly and indirectly, of a large percentage of the village population, came to an end.

The first third of the century was marked by the deepening of a long agricultural depression that had its roots in the last quarter of the previous century. World War I brought a temporary reprieve but the 1920s and 1930s were desperate times for many. The depression was finally ended by World War II which also accelerated new ways of working including mechanisation and an increase in land under cultivation.

The post-war years were initially concerned with productivity and efficiency. Small fields were amalgamated. Scientific developments were made in plant breeding and the development of artificial fertilisers and pest controls. Towards the end of the century there was a shift towards conservation and land stewardship and some of the earlier post-war measures were reversed.

The Farming Context

From an agricultural perspective, Ludham has a number of natural advantages. The village is large, covering an area of around 3000 acres comprising deep fertile soils on gentle terrain and extensive grazing marsh on the silty-clay floodplain of the rivers Ant and Thurne. The upland of the areas forms part of the ‘Flegg Loams’ farming region (Wade Martins and Williamson, 2005, p.115) which is recognised as containing some of the best arable land in the county. There are also smaller areas of former peat extraction such as around Womack Water and at How Hill where reed and sedge are still harvested.

Aside from these natural advantages, easy access to the rivers Ant and Thurne was still important for trading purposes in the early part of the century. In fact the trading wherries were still in evidence at the village staithes into the 1960s.

Land Ownership

In the period up to the First World War, Norfolk was a county of large landowners and tenant farmers. It was estimated that less than one farmer in six owned the land he farmed (Douet, 2005, p178). Much of Ludham was owned by absentee landowners who used a farm bailiff to farm on their behalf but who also leased their smaller farms to tenant farmers. The major landowners in Ludham at the beginning of the twentieth century were listed in Kelly’s Directory of 1900 as:

Thomas Slipper of Braydeston Hall;

Trustees of the late William Augustus Page of Oby;

Ash Rudd of East Ruston Hall;

Alfred Neave of Great Yarmouth;

Trustees of the late Aaron Neave;

William Frederick Green of Wroxham.

Others listed as farmers were either the bailiffs or tenants of the above or farmed in a small way. The 1901 census shows that several of the farmhouses (Green Farm, High House, Beeches Farm and The Laurels) were then privately let as family or holiday homes. Grange Farm had been sold in 1896 and the house became a private home of the Fitz-Hugh family.

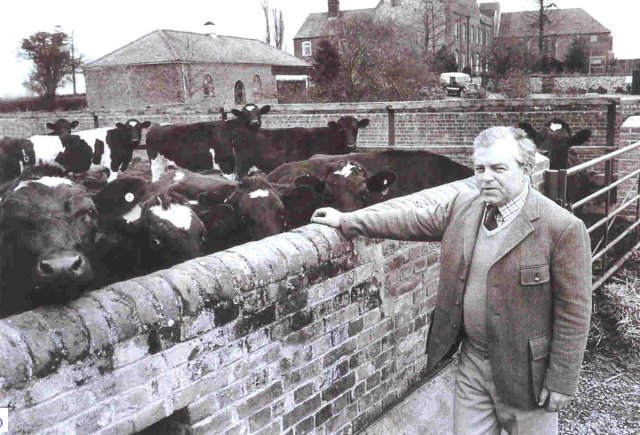

The century had begun with the death in 1900 of William Heath, formerly of Ludham Hall. Heath had been a dominant figure in local agriculture in the previous century. At one time he farmed over 2000 acres across several villages and was a regular fixture, exhibiting his prize Hereford cattle, at national agricultural shows.

Since his retirement from farming in the late 1870s, the Ludham Hall farm had been farmed by Thomas Worts of Mill Farm, Sutton through his bailiff Richard Gibbs. Of the other major farmers, two, Thomas Slipper and Alfred Neave, had once lived in Ludham (at Fritton and High House farms, respectively) but had become absentee landowners during the 1880s. Alfred’s brother Aaron Neave had died in 1884 and his land (The Laurels, Manship’s and Page’s Farms) was leased out by his executors. William Green of Wroxham owned Beeches Farm and Ash Rudd of East Ruston Hall owned land in the west of the village.

The early years of the twentieth century saw a high volume of land transactions. The Norwich architect Edward Boardman bought 190 acres from the Page family and began to establish the How Hill estate. In 1904, he acquired Gt Reedham and Turf Fen from the Poors’ Trustees and gradually added a number of other properties that adjoined his holding until his estate totalled some 872 acres (Holmes, 1988, p.6).

Both Alfred Neave and Ash Rudd died in 1908 leading to the sale of their Ludham estates. High House Farm was initially offered for sale in 1908. It was then for sale again in 1914 along with Green Farm, Walton Hall Farm and Bower Farm in Potter Heigham. In 1910, Whitegates Farm was sold and in 1912 Whitehouse Farm followed.

Alongside Edward Boardman, the other major figure to arrive in the village in the first half of the twentieth century was William Wright, originally from Moulton St Mary, but then farming from Upton Hall.

|

He acquired both Whitehouse and

Whitegates farms and took over the lease of the Ludham Hall estate from the Worts family c.1911. Ludham Hall was unoccupied at the time of the 1911 census and was probably undergoing major work ahead of the Wright family’s arrival. The house was re-roofed at this time and some attached cottages were replaced with the one that now stands facing south today. Shortly after his arrival, Wright was instrumental in the construction of a new Methodist chapel in nearby Johnson Street. |

According to his 1958 obituary he went on to farm over 2000 acres in Ludham and nearby villages as well as being a Magistrate and County Councillor.

Crops

For the first third of the century, contemporary trade directories tell us that the principal crops grown in Ludham were the grain crops – wheat, oats and barley. Oats were grown primarily to feed the working horses and were to disappear with the demise of horse power.

Harvest time was a significant focus in the rural calendar. At harvest time, corn was cut down by a horse drawn reaper or binder. The bundles of cut corn were stood upright to dry in groups of 8-10 forming what were known as ‘shocks’ or ‘stooks’. The corn would then either be threshed (or thrashed) to extract the grain, straight off the field or carted away to a stackyard where it was formed into thatched stacks until such time as the threshing could be carried out, usually during the winter. Stubbles were traditionally left after harvest and ploughed in the New Year ahead of spring sowing.

Larger farms had their own threshing tackle. It has been claimed that Ludham Hall was the first farm in Norfolk to adopt steam threshing in the nineteenth century. More usually the threshing teams were mobile and moved from farm to farm. One of these threshing contractors, Cyril Bensley, was based in Fritton Lane in Ludham.

Although there were odd examples around from the 1930s it was not until the 1950s that combine harvesters, which combined both the cutting and grain extraction processes, became commonplace.

A major crop development was the introduction of sugar beet which was grown under contract to newly built factories and replaced fodder crops such as mangles and turnips as the break crop. Sugar beet was particularly labour intensive. It was ‘singled’ which meant manually hoeing to ensure only one plant per spacing. Harvesting was also hard work. The beet was lifted manually by a two tined fork, often from hard ground in cold conditions, until new harvesters were adopted in the 1950s.

Aside from the more common crops, a fruit and poultry farming operation was established by Edward Boardman’s son Stuart at How Hill Farm in the 1920s.

Farming the Marshes

Dairying was on the rise in the first half of the twentieth century. By 1939 the county had become a major milk producing area. The local cattle breed was the Red Poll, a dual purpose milk and beef cow. The Scots families who moved into the area brought Ayrshires, another dual purpose cow. However the dairy industry became increasingly specialised in the twentieth century and the familiar ‘black and white’ dairy cow that were either Friesians, Holsteins or a cross of the two, became commonplace. Some villagers still recall the practice of driving cattle to Ludham from Norwich cattle market or Wroxham railway station.

The marshland in the village was ideal for both fattening stock and dairying. The marshland had been wet common until the end of the eighteenth century. Parliamentary Enclosure 1800-1802 set up a drainage commission and established the two main drainage mill sites - Bridgefen (which drained marshes both sides of Ludham Bridge and Horsefen. The windmills, established by the drainage commissioners, albeit much modernised, were still operating in the early part of the twentieth century.

Additional mills were also built by private individuals during the nineteenth century on the Horsefen marshes, Coldharbour marshes, to the north of Ludham Bridge and at How Hill. Steam-powered turbines were installed by the commissioners at Horsefen and Bridgefen in the late nineteenth century, providing auxiliary power when the mills were not operational. This arrangement continued until the adoption of oil engines in 1919 at Horsefen and 1926 at Bridgefen and even then the windmills were not immediately decommissioned.

The last marshmen to look after the drainage mills and engines were Charles Howell, Charles Banham and Charles Beaumont at Ludham Bridge and James Ewles, John Ewles and Alfred Goodwin at the Horsefen site.

The Agricultural Depression

The period between the wars was marked by a depression that had begun in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, caused partly by a run of terrible weather in the 1870s and then by imports of cheap grain and later refrigerated meat. The resulting agricultural depression continued into the twentieth century and worsened during the twenties and thirties. Poor prices were reflected in lower farm workers wages and assisted passage was given for those prepared to emigrate for work. Significant numbers of people were leaving Ludham and the surrounding villages into the 1920s (Snelling 1999, pp.168-169). The late Clifford Kittle of Green Farm could recall land in Ludham costing just £15 an acre. In Potter Heigham too, land was changing hands for between £14 and £17 an acre (Howard, 1997, p.23).

The dire economic situation provided an opportunity for some. Some tenants were able to purchase their farms. In fact the proportion of those who owned the land they farmed increased from 10% in 1914 to 36% by 1927 (Wade Martins, 1987, p.118).

New families who were used to farming in challenging conditions, moved into the area. The Mattocks family had moved south from Cumberland settling first in Burlingham and then moving to Ludham in the early 1900s where they farmed Laurels and Pages Farms. Their strong regional accents are still remembered by the older village residents today. In 1921, following the death of William Mattocks, the farms were offered for sale on the instructions of the daughters of the late Aaron Neave, who had a life interest in the property (then totalling 369 acres). The Mattocks family acquired The Laurels and Edward Boardman bought Page’s Farm which he then leased to the Mattocks family.

There was also an influx of enterprising Scots families into the region assisted by cheap loans from the Bank of Scotland. The Ritchie family originally took over land in Suffolk, bringing their livestock with them on the train. After WWII they took over the tenancy of the Ludham Hall farm and established a successful farming business there in the second half of the twentieth century.

County Smallholdings

The depression and a drive to find employment for returning soldiers following WWI led Norfolk County Council to develop its smallholdings’ estate. In 1921, the Norfolk County Council smallholdings’ committee acquired Bower and Rose Farms in Potter Heigham along with Fritton Farm in Ludham in order to convert them into smallholdings. These were initially designed as 20 acre units to support one man and one horse. On the Fritton Farm land, seven plots with wooden bungalows were established on what was later to become the airfield. Four further holdings were created between Fritton Lane and Yarmouth Road. Kelly’s directory of 1929 lists 12 Ludham men as ‘smallholder’ along with another as farmer at Fritton House. Ultimately their size and the depression meant they were not economically viable and these smaller holdings were gradually amalgamated.

The War Years

|

The war effectively brought an end to

the farming depression and accelerated many other

changes to farming practice. Tractors became

commonplace. The Government secured a supply of

tractors under the lend-lease scheme to help

increase UK productivity. The Goodwin family at High

House Farm apparently had a tractor in 1936. However

most of the farms in the village acquired their

first tractors during the war years. The Mattocks

family at Laurels Farm were the last to hold out,

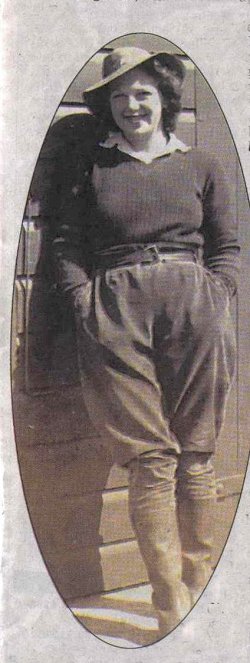

farming with horses only until 1955. The War Years saw further transformations in the village landscape. At Fritton Farm a number of the 1920s smallholdings were taken over to create Ludham airfield at end of 1941. An Army camp was built on land on both sides of School Road as well as in the Manor Grounds. Ludham Hall was taken over as a Land Army hostel and training centre where trainees would come and spend a month learning basic skills before taking up their placements on local farms. Joan ‘Pop’ Snelling was one of Ludham’s land girls and was based at Hall Common Farm. There, she experienced what was to be the tail end of many traditional farming practices. She has published an account of her time as a ‘land girl (Snelling, 2004). |

|

The Post War Years

The war years effectively marked the end of traditional farming. After the war, the emphasis on productivity and efficiency increased. The 1947 Agriculture Act was designed to ensure stability through guaranteed prices and assured markets. It was intended that this would encourage farmers to invest in their farms.

Food rationing did not end until 1953 and farmers were encouraged to take advantage of scientific developments to maximise yields. Grants were offered to plough up grassland. Artificial fertilisers replaced the manual spreading of farmyard muck. Pesticides were also developed and in 1968, Westwick Distributors established a crop spraying business on the Ludham airfield.

Direct employment on farms significantly reduced and with that the tied cottages that the farmworkers had lived in. Farmers increasingly brought in contractors with machinery to carry out work. Farmers also operated through buying groups and co-operatives to reduce costs. In Ludham the ‘Wri-Brook’ farming partnership (between the Wright and Brooks families) was established in 1960s to farm the High House, Beeches and Whitegates Farms.

The appearance of the village continued to change. Farmers were offered grants to remove hedges and create larger, more efficient fields. A number of farms were amalgamated and farmhouses sold off. New farm buildings were constructed from modern materials on a more industrial scale to suit large, modern equipment and storage requirements. Many traditional farm buildings were no longer used for their original purpose and were converted to residential or holiday accommodation.

In 1973, Britain joined the European Economic Community (EEC) which brought in a complex system of compensation designed to keep prices similar across member countries. This made grain production highly profitable and led to a boom in production. It also made the conversion of marshland to arable land an appealing prospect for farmers. Some of the village marshland had been temporarily put under the plough during the war, although accounts differ over whether this was successful or not. The marshes in Ludham were drained by electrically powered pumps by the 1950s.

In the 1970s and 80s there were further developments in land drainage with the availability of plastic piping. These developments led to various schemes to drain and then cultivate marshland right across the Broads Area. The outcry this caused made it to the national newspapers and ultimately led to the scheme to compensate farmers for profits foregone known initially as the Broads Grazing Marshes Scheme. The Halvergate Marshes were later to be declared the first Environmentally Sensitive Area or ESA in the country.

Conservation

There was a general shift from the 1980s from support for production towards support for conservation measures.

Two wetland areas of Ludham became managed primarily for their conservation interest in the 1980s. Following the death of Edward Boardman in 1950 and his widow in 1960, the farming side of the How Hill estate was split from the 344 acre residential and wetland estate which the family reluctantly put up for sale in 1966. It was bought by Norfolk County Council’s Education Committee to form a residential education centre. However, in 1983, after Norfolk County Council had decided to close and sell How Hill, the estate (minus the house and its immediate surroundings) was sold to the Broads Authority.

In 1983-4, the majority of the Horsefen Marshes were sold to the Nature Conservancy Council. These were recognised as being of prime ecological importance and declared a National Nature Reserve in 1987 (George, 1992).

Grants to remove hedgerows were ended in 1983 and by the end of the century new Countryside Stewardship schemes brought new incentives to revert arable land back to grass and to plant new hedgerows. This saw a number of new hedgerows planted – notably on Ludham Hall Farm.

As income from the traditional farming activities of the area declined, farms in Ludham specialised and diversified. Some had been doing so for many years e.g fruit and holly growing operations at How Hill Farm. Other activities such as pig rearing were done on a much larger scale than before. The location of the village within the Broads provided opportunities to diversify into leisure and tourism related activity. Holiday cottages were established at Ludham Hall and Manor Farms, a caravan and campsite at Beeches Farm and a leisure complex at High House Farm (more?). Aside from this, the village still ended the century, with a working, farming landscape.

Grateful thanks go to Alison Yardy for researching and writing this chapter.

Sources

Kelly’s Directories 1900, 1904, 1908, 1912, 1916, 1922, 1929, 1933, 1937

Minutes of Ludham Drainage Board

1901, 1911 Census returns

NRO TBC

Bibliography

Douet, Alec, ‘Agriculture in the 20th Century’ in Trevor Ashwin and Alan Davison eds. An Historical Atlas of Norfolk (Chichester: Phillimore, 2005), pp. 178-179

Fuller, Mike, Fritton Road, Ludham and Ludham Farms: 1900-2000 (Ludham Community Archive Publications, 2005; 2008)

George, Martin, The Land Use, Ecology and Conservation of Broadland (Chichester: Packard Publishing, 1992)

Holmes, David, The How Hill Story, (Ludham: How Hill Trust, 1988)

Howard, Samuel, The Parish of Potter Heigham, (Hemsby: Desne Publishing, 1997)

Nicholson, Jimmy, I Kept a Troshin; More Muck than Money (S J Nicholson, 1989; 1991); Steam Men of Yesteryear (Reeve, 1994)

Pollitt, Michael, ‘The Land’ in Norfolk Century (Norwich: Eastern Counties Newspapers, 1999), pp. 123-139

Snelling, Joan, M., Ludham: A Norfolk Village 1800-1900 (Potter Heigham, E. Mumby, 1999); A Land Girl’s War (Ipswich, Old Pond Publishing, 2004)

Wade Martins, Susanna, A History of Norfolk (Chichester: Phillimore, 1987 edition)

Wade Martins, Susanna, and Tom Williamson, ‘Norfolk Agriculture 1500-1750’ in An Historical Atlas of Norfolk (Chichester: Phillimore, 2005), pp.115-116; A Countryside of East Anglia: Changing Landscapes, 1870-1950 (Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 2008)