|

|

Chapter

1 Life At The Turn Of The Century In Ludham 1900-1910  How Hill House under construction 1904 |

The village of Ludham is a short distance from the Norfolk coast and has been the centre of rich farming land for over a thousand years. It is surrounded by rivers and marshland and has Womack Water, Ludham Bridge and How Hill Staithes on its doorstep thus ensuring that in the past there was a steady flow of trading wherries calling regularly at the village staithe in the early part of the 20th century.

From an agricultural perspective, Ludham had many advantages. The village covered some 3000 acres made up of deep fertile soils on gentle terrain with extensive grazing marsh on the silt and clay floodplain of the Ant and Thurne rivers.

There were also smaller areas of former peat extraction such as around Womack Water and How Hill where quantities of reed and sedge harvesting could be seen, a practice that continued into the 21st century.

Ludham has a timeless quality about it but during the 20th Century, it went through a plethora of changes. Its roots have always been firmly fixed in agriculture and in 1900 many farms created work for the local population of 639. The rural living standards at the beginning of the 20th century were very poor as agricultural workers were among the lowest paid with an income barely half that of the national average wage. Many of these workers were employed on a casual basis and without the mechanisation we now associate with farms, they had a very hard life.

As you read through this book you will see that during the twentieth century agricultural employment and farming techniques in general were set to change the lives of a large proportion of the village.

Farms were gradually changing at the beginning of the century; arable farming was not so profitable when cheap imported wheat from abroad began to steadily invade the home market. Nearly all of the farms around the area were run by tenant farmers as most of the parish land, according to Kelly’s Directory for 1900, was owned by 6 absentee landlords who often employed a farm bailiff to farm on their behalf. Ash Rudd of East Ruston Hall owned a large parcel of land in the north-west of the parish, once known as How Field. Thomas Slipper of Braydeston Hall whose family had once lived and farmed at Fritton Farm, owned all the north-east of the parish, known as Ludham Field and was farmed by a bailiff called James Beevor.

Alfred Neave, who lived in Great Yarmouth, owned four farms, three of which formed the old open field of Bears Hirn. These were: Beeches Farm, Green Farm and High House Farm. He also owned The Laurels farm in the centre of the parish. Clint Field was owned by Thomas Worts of Horning Hall and he had a bailiff named Richard Gibbs. The Ecclesiastical Commissioners still owned the Ludham Hall estate and the Goose Croft lands were owned by Robert Bond of Norwich, this included Manor Farm, Coldharbour and Hall Common Farm, where his family had lived.

Let us consider what the farm workers’ jobs entailed to give us a better idea of their working life. There have always been crop fields in the area and a farm hand in the early twentieth century was an expert hand hoer. He would be as economical as possible and use as few strokes as possible to disentangle twisted stems and leave single plants free from weeds and the correct distance apart. The weeds were for example knotgrass, coltsfoot, fat hen and wild mustard. It would take several days to hoe a field of beet.

The stables were the centre and power house of the farm in 1900 as the land was ploughed, harrowed, drilled, rolled and harvested with horse drawn implements. A horse drawn flail cutter was probably used to produce the sheaves which characterised the harvest fields then, but haymaking relied heavily on the use of the scythe, the pitchfork and muscle power.

There may be a nostalgic beauty about the scene of a horse drawn plough that cannot be replicated with a modern tractor but both produce that very iconic farmland sight of scavenging birds following the plough. Walking behind the plough with one hand on the plough handle and the other on the plough line, up and down, furrow after furrow, hour after hour, day after day may seem very monotonous but it took a lot of concentration and the plough hand would know exactly where in the field he was just by the sound of the share in the ground or the smell of the earth. Of course he also had to put up with the acrid smell of the sweating horse.

In the dairy there were no milking machines, just farmhands brought in from whatever job they had been doing to lend a hand. Hygiene may not have been the order of the day either. Virtually no washing of hands before milking the cow and the cow sheds possibly deep in cow muck and grease from the animals. It didn't matter too much if the milk appeared a little dirty in the pail as it was cooled and strained anyway! In more modern times cowsheds would become concrete and steel, and smell of chemicals, detergents, insecticides and sterilising agents.

The farmhand often had to be a jack of all trades and be able to do everything from looking after the horses, their tack and farm implements to acquiring all the agricultural and husbandry skills and knowledge of the countryside. He would understand that the wooden wheels of carts shrank during dry spells and would have rolled them into the farm pond to soak before putting them back onto newly greased axles. This would have made them swollen with water and tight and safe to use. Lunch would be in the fields sitting against a hedge with chunks of bread and a little cheese and cold tea and the talk would have been about the farm work and the weather rather than what we think of as modern topics of conversation.

At the end of the nineteenth century the Page family were in possession of How Hill as tenant farmers. They regularly dug sand and gravel from the hill to build up the tracks and farm yard. The last of the How Hill eel catchers, Ben Curtis moved out of Toad Hole Cottage.

In 1902 Mr. E. T. Boardman negotiated and bought one hundred and ninety acres which included the hill, the mill which was disused, mill house and farmland down to the river. He later acquired more land until the estate was eight hundred and seventy two acres in all. He designed the house to be all white with coloured decoration and all bedrooms and the living room had windows facing south. Although the date over the door is 1904 they did not have full occupation until April 1905.

How Hill house was much smaller in 1904 than it is now.

Up to WWI this was their ‘holiday home’. The Woolstons were guardians of the property and lived in Mill House. It was Walter Woolston who explained many of the secrets of natural history to the Boardman children as they grew up.

What was Ludham village life like in 1900? Well, take away the electricity, piped water and piped sewage. Remember that there were no mechanical aids in the home such as washing machines, microwaves, electric or gas cookers, vacuum cleaners, electric irons and freezers: tinned, frozen and convenience foods were yet to come in: cars and buses to get to shops and local towns and mechanised farm machinery had not yet taken on any significance. Luxuries such as television or the internet were unheard of and even the telephone would probably not have reached the village yet. We can then begin to appreciate that everyday life was quite different.

Norwich Road

Domestic life was sometimes gruelling and heavy daily chores for the housewife were major tasks in the week taking up time and energy. The family wash for example, traditionally done on a Monday was a ritual of lighting the fire and heating the water that had to be fetched from the well. Then came the soaking, boiling, washing, starching and rinsing before hanging everything out to dry. Everywhere steam, and baths of water with the housewife's hands becoming raw from the rubbing action needed to clean the clothes. The following day entailed the ironing with flat bed irons heated over the fire. This heavy hot work caused many a sooty mark on clean clothes or nasty burnt fingers.

There were no convenience foods as we know them. Everything was home-made and often home produced. There were baking days using coal and wood fuelled ovens and the Sunday joint was often cooked using a local trader’s oven. The land supplied the food and treats such as blackberries, chestnuts and walnuts were picked from hedges and trees whilst wild rabbit and pigeon made wholesome meals. Honey from wild bees and butter and milk straight from the farm were the order of the day. Households grew their own vegetables and some had their own chickens and pigs to help feed the family. One cannot get away from the fact that in many ways they had a healthy diet, a trend which continues into modern times.

During the early years of the century transport used in the village was mainly horse and cart. Wagon or tumbrel type carts were used by tradesman and the farmers for fetching and carrying.

Roads which of course were unmade soon became impassable after heavy rain and carts quickly sank up to their axles in the mud. The cottages on the Yarmouth Road, opposite the Bakers Arms, were often flooded as water ran down the road. There were no gutters or drains to take away excess rain water then. For the ordinary folks it was a pony and trap to take the family out to town. We should remember that it would have been an all day event going by cart to Norwich. A farmer or gentleman of the parish would have a hunter or a fine horse as became his status within the village.

As the car had probably not reached the rather isolated village at this time walking was an everyday mode of travel and residents could walk to the local railway stations at Catfield or Potter Heigham to get further afield. School children had day trips to the seaside by horse and wagon which was always thought of as a very special day out.

A school outing in the How Hill cart.

As you can see, there must have been an abundance of horses in the village and this links up with the number of ponds within the village at the time. There was a pond at ‘Pit Corner’ at the commencement of Horsefen Road and this was known as Beech Farm horse pond. Where Willow Way is today there was a pond in the meadow where horses were kept at night in the summer. All the farms seemed to have a pond of some size for their animals and this, as well as the marsh being frozen over, may have given rise to skating during the winter months. Womack Water often froze over enough for skating on in those days. Some of the ponds still exist and if you travel along Fritton Road to the corner opposite Fritton Farm house there is an original large pond which has been maintained.

Because of transport issues there was a call for many businesses to operate within the village to meet the needs of the community. It would have been a time of prosperity for some in the village and offered the residents all the vital commodities necessary for daily living.

At the corner of School Road and The Street can be seen a building which is still known as Cooks Corner (after the owners in the 1920s). This building, believed to be the oldest dwelling in the village, was originally known as Town Farm and owned by Aaron Neave and in 1908 Robert Allard opened a Cycle Agency there.

It later became a grocery shop operated by Harriet England. This change of business possibly came about because of the competition from H. D. Brooks’ cycle shop across the road. The grocery and general store lasted for the next eighty years.

H. D. Brooks had already established his cycle shop on The Street in the early 1900s. He operated from a small building (it is still there, called The Cats Whiskers) in which he did cycle sales and repairs as well as shoemaking. The shoemaker business was later taken over by Mr Clarke and H. D. Brooks moved his business up to Catfield Road and ran his business from a building near to Folly House, opposite the Methodist Chapel.

The business was successful and two petrol pumps were later added as the business expanded into a garage to cater for the needs of the motor car.

Looking around the Ludham area, the ruins of many windmills can be seen: but only a fraction of those which once stood in the area. At the start of the twentieth century, these mills were vital parts of the local economy, grinding corn, but more importantly driving the pumps which drained the marshes.

Many of these mills were designed and built by the England Millwrights. The offices and workshops of Edwin England stood on The Street in 1900. At the end of the century the area had been developed into a garage and forecourt.

Beaumont's Mill near Ludham Bridge

England’s was a well established and respected business, building, improving and maintaining mills over a wide area. This old Ludham family had been in the mill business for generations and were an important local employer. They were at the peak of their success as a business at the beginning of the twentieth century. Daniel England was the inventor of The Patent Turbine for Fen Drainage, an important device in the wetlands around Ludham.

On the opposite side of The Street from England’s, on the site which later became Thrower’s Car Park, stood the butchers shop of William England, butcher and slaughterer. The names William and Daniel appear in every generation of the England family. A fine family tradition if somewhat confusing for historians.

In those days, the slaughter man would visit local farms and the meat products would be sold locally. This site continued as a butchers shop for the next 65 years.

This shop (now demolished) was England's Butchers

Next door to the butchers, A. T. Thrower opened a new grocery shop in 1902. He was told by his competitors in the village that this new enterprise would not last a year.

However, the business prospered and in 2002 celebrated its centenary, still operating in the Thrower family. It was a more modest affair back then with a shop and local delivery service.

Opposite Throwers was a general store, listed in 1904 as being operated by Harriet Bond. We do not have a picture of the shop as it used to be. Below is a picture of Bond’s Store in Norwich which was owned by other members of the family. In the early part of the century the Ecclesiastical Commissioners still owned the Ludham Hall estate and the Goose Croft lands were owned by Robert Bond (of Norwich) and included Manor Farm, Coldharbour and Hall Common Farm, where his family had lived.

Next door to Throwers shop stood The Baker’s Arms. This beer house had been operating since 1842 and sold Bullards Ales and Stouts. In 1900 the landlord was John Davey. The Bakers Arms also had rooms to let which would have been used by travelling salesmen and other visitors to the village. The Baker’s Arms sold only beer and had no pumps. The landlord had to go down into the cellar every time a pint was ordered and he was sometimes a bit reluctant to go down just for one drink preferring to wait until several had been ordered. This pub also incorporated a bake house where local people could bring food to be cooked in the oven. This building is no longer standing, having been demolished in 1959. The place where it stood became known as Bakers Arms Green.

The King's Arms

Opposite The Bakers Arms was the King’s Arms pub. The King’s Arms was known to be opened in 1836 and continued to operate as a pub and restaurant well into the 21st century.

The outside appearance is little changed from the one which would have been familiar to Ludham people in the 1900’s. Daniel Chasteney England was the landlord from 1883 starting an association with the England family which would last until 1922. Edwin William Daniel England took over as landlord in 1900 and this must have been in addition to his duties at the England Millwrights next door.

At the end of The Street near to St. Catherine’s Church stands Crown House. This old building had many uses in the twentieth century, but as the century began, it was the Rose and Crown Pub (sometimes just known as the Crown). The pub had been established for a long time and there is a record of it in 1752. In 1900, Eldred Slaughter was succeeded by Sarah Slaughter as landlord. Shortly after this, the pub closed down.

A cart stops outside Crown House

In 1907, Ebeneezer Newton established his business in the old Rose and Crown premises. Ebeneezer was a Miller and Corn Merchant as well as a Carrier and Shipping Agent. Supplies arrived by wherry at Womack Staithe or by train to Potter Heigham. The shipping agent part of his business dealt with emigration and here, you could arrange to start a new life in other parts of the world.

At Potter Heigham Halt

A trading wherry in Womack Water, Ludham

The Grocery and Drapery shop owned by Grace Lyon from 1904 before passing to the Powell family and then the Hudson Family. It was later the Dairy Cafe and then a butcher’s shop.

The village Post Office was located next to the entrance gates to the churchyard. In 1908, J. W. Dale was the post master. The post office had been previously located in Crown House and also in a thatched cottage opposite the church in Norwich Road. However, the shop next to the church gates was to be its home for the next 80 years. The building is still there and is known as the Old Post Office even though it was later used as a bistro.

The Post Office

In the early 1900’s, Staithe House in Staithe Road was the wherry harbour where supplies for the village were unloaded and stored in warehouses. Wherries used all of the Ludham staithes, which included Staithe Road, Horsefen Road, Ludham Bridge and How Hill. Much of the material carried was for the agricultural sector, particularly grain and sugar beet, as well as chalk, lime and vegetables for market. Reed and sedge were frequently carried as well as marsh litter. Marsh litter as a tradable commodity died out quite rapidly with the decline of the horse as an important transport medium. Heavier goods such as timber, coal and bricks were also carried, as well as general stores. Even moving house was known to be done by wherry. These trading wherries were about 20 – 25 tons in size as larger ones could not navigate the smaller rivers.

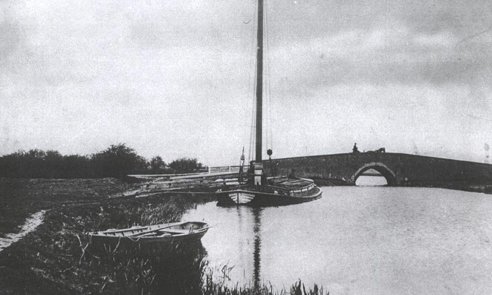

Wherry at Ludham Bridge

Frequently, lighter goods and people, were transported by carriers.

At Womack Staithe in Horsefen Road stood, the Maltings, a large storehouse, and next door were kilns for brick making using materials quarried near to the site. The kilns were out of use by the beginning of the twentieth century, but then provided the local children with an interesting play area.

The maltings with the old brick kilns to the right

The Maltings at Womack Staithe

In 1891 H. R. M. Harrison had bought several cottages, the boat builders shop, stables, buildings, yards, gardens and parcels of arable pasture , marsh land and ozier beds around the staithe. When he and his family emigrated to America in 1907/8 the land was split up into Fenside with a barn, Womack House with stables and the Boatyard with Misty Morn. Very little is known about boatbuilding in Ludham at the beginning of the twentieth century. The trading wherry Zoe had been built at an open workshop, part of the farm owned by Robert Harrison for Riches of Catfield so one could assume that small scale work had also featured along the banks of the dyke.

Next door to the King’s Arms in Norwich Road stood the shop and premises of Samuel Knights, Harness Maker and Saddler. By the end of the century the shop was in use as a tea room. Horse power was very important to the farming industry and the local population so this shop provided essential services. Next door and to the rear of the cottages were the workshops of the blacksmith, Percy Salmon and often one would have been aware of rhythmic ringing of the nails being hammered in place .

Len Bush fitting a tyre to a wheel

Carpenter and Wheelwright Len Bush also had workshops here and we should pause a while to appreciate the real craftsmanship that was in regular use. Here would be a workshop with benches and an array of tools such as chisels, planes, saws of various grades and vice like clamps. There would have been a forge worked by bellows to get white hot coals roaring. Len Bush would have held iron wheel rims with long tongs beating them into shape with his heavy hammer. Hot metal would have been cooled with water, sending up clouds of hissing steam. Working conditions in these places were very basic, often being dark, dirty, no nonsense establishments. Most of the work done was probably outside under lean to shelters against the weather. There was even a useful stone outside to help you get back on your horse. A stone (actually an erratic left by a glacier in the last ice age) can still be seen.

Next to this was The Limes cottage (still there). In the outbuildings of this cottage, Fred Thrower, Coal Merchant and Pig Farmer had his business. In the early days Fred Thrower with his horse and cart collected the coal from Potter Heigham coal yard and delivered it to all the surrounding villages.

Ebenezer Newton also had a coal round in Ludham. He also sold paraffin oil by the gallon, from a tank with a tap and using a measuring can, transferred the paraffin oil into the customers own cans.

At the rear of Glenhaven cottage on Norwich Road was a smokehouse for fish and Eldred Slaughter, Fish Dealer (and Rose and Crown landlord) had his premises at No. 1, Alma Cottages.

Near to Ludham Bridge is the small hamlet of Johnson Street. Here stands the Dog Inn, a free house which has been a pub for many years. There is a reference to a building on this site called Dog House in 1689 and the pub was known to have been operating in the 1820’s. In 1900, the landlord was Thomas Smith.

The Dog Inn

Ludham Methodist Chapel

Ludham Methodist Chapel

The chapel at High Street entered the twentieth century having just survived a fire. Although little is recorded of this event it seems that an oil lamp caused the problem. Documents show the correspondence between the local church and Methodist headquarters as well as the invoices of Grace Lyons and a local carpenter, Jacob Dale. It seems from the invoices that the fire was localised, but damaged a number of wooden panels as well as carpeting, mats and some hassocks. A new oil lamp was also required. The High Street Chapel was originally attached to the Great Yarmouth Wesleyan Circuit. This circuit was made up of the Denes Chapel and the Mission Hall in Yarmouth, the Gorleston Chapel, two Chapels in Caister (the West and the East Chapels), Ormesby, Stokesby, Ludham, Fleggburgh, Wickhampton, and Acle. In the first few years of the century a Twentieth Century Fund was organised. There are no records existing to show the purpose of the fund but it was recorded in the Quarterly Plan of February to May 1900 that:

Friends who have made promises to the fund are respectfully requested to pay in their contributions as early as convenient to the Circuit Ministers or Circuit Stewards.

Further contributions are earnestly solicited.

In the Quarterly Plan for August to November 1900 it was noted that £420.00 had been raised to support this fund. That would have been a considerable sum in those days. In 1903 High Street Chapel Ludham had thirty five members and contributed £1.17.31/4 to the Circuit through its weekly collection. Weekly services were at 2.30 p.m. and 6.30 p.m. on Sundays and once each quarter on Tuesday at 7.15 p.m. At this time there were very few local or visiting Preachers based in the village, or indeed, in any of the surrounding villages, most coming from Yarmouth, Gorleston and Caister. In 1909 Mr. L. J. Hiner came as a Visiting Preacher to Ludham, lodging with the High Street Steward, Mr. W. Lake. Mr. Hines became Lay Agent for the Circuit from 1909 to 1910 when he left. In his place came Mr. E. C. Gimblett. He also lodged with Mr. Lake and fulfilled the same roles as his predecessor from 1910 to 1911. In 1913 it was noted that Mr. H. Helsden of Walton Hall Farm was a visiting preacher.

At the turn of the first decade of the century the congregation attending High Street had fallen to about twenty and by 1916 were around twelve. It was noted in the Quarterly Plans of this era that the offerings from one service each quarter were to be allocated to the Horse Hire Fund. No other details of this are noted.

Little has been recorded about the Baptist Chapel in Staithe Road. A Baptist Minute Book (NRO) indicated that the Ludham Chapel and the Martham Chapel were linked and that for the half year ending June 30th. 1902 it was voted on and agreed that the sum of £3.16.6d should be paid for the conveyance of preachers from Yarmouth to Ludham and again on December 11th. 1902 it was recorded that on December 31st. 1902 the Secretary was authorised to pay the account for the conveyance of Lay Preachers from Yarmouth to Ludham, although no sum was mentioned. The same Minute Book records that a representative from Ludham attended the Sixty Ninth Annual Assembly at St. Mary’s Chapel, Norwich on the 15th. May, 1902. There were twenty eight Pastors at the conference and sixty six delegates. On March 17th. 1904 a grant was made available to Ludham and Martham Chapels on the condition that they raised £30 themselves. In the minutes for September 23rd. 1904 it is recorded that Rev. C. A. Ingram was to be invited to the Pastorate of Martham (and Ludham?) and in March 1905 it is recorded that Martham and Ludham are satisfied with him. The last entry that refers to the Ludham Chapel was in a Minute for the meeting of December 9th. 1909 when Messrs. Cowe and D. J. John reported by letter that an afternoon service only was arranged for at Ludham to be supplied by preachers from the neighbourhood, so saving expenses.

The Strict and Particular Baptist Chapel

St Catherine’s Church has always gracefully dominated the village of Ludham. As Ken Grapes, the Church Warden has so eloquently written, it has stood in the centre of Ludham for some six centuries, providing inspiration for the village and watching over the births, marriages and deaths of its inhabitants. Long may it continue.

The historic tympanum had been recently replaced at St Catherine's

At the beginning of the twentieth century painted boards depicting the crucifixion were discovered in a blocked off section of the church. They were wrapped in a canvas painting of the Arms of Queen Elizabeth, and both must have been quite a thrilling find. Early in the century they were put back into the tympanum arch for future generations to appreciate. A considerable amount of restoration work was undertaken in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century which we can all now enjoy.

At the turn of the century Dr James Alexander Gordon JP LRCP LRCS (Edin) LM was the medical practitioner for the area. He had arrived in Ludham at the age of 27 in 1879 and was to remain until 1918 giving his services to the community for 39 years. He ran a singled handed practice over a wild and scattered community stretching from Wroxham and Horstead to Sea Palling and Happisburgh. He resided at Ludham Manor and as begets his status he had a rather dashing Arabian horse. This horse according to C. F. Carrodus in the Eastern Daily Press was a goer. Dr Gordon was known to ride from Ludham Manor to Wroxham Station in seventeen and a half minutes! He was an Ulster man of Scottish decent with a strong, forceful, breezy unconventional personality and became well known both in Norwich and Great Yarmouth.

He had many curious experiences which can help give us an insight into some of the old ways of thinking by the local people at the turn of the century. He related several of these incidences to C. F. Carrodus. He writes in the Eastern Daily Press that Dr Gordon when he first started up the practice had been approached by a hard working mother who lived in a small thatched cottage at Ludham Bridge.

She complained that her son had bewitched the butter churn as there had been no butter for weeks. “But surely not little Bob?" "Yes" she had replied. The doctor then asked for a kettle of hot water and took a turn at the handle himself and soon there were lumps of butter splashing about in the cream. She was not aware that the temperature mattered and insisted that the doctor had broken the spell. The story of this new medicine man soon spread far and wide. According to Edward Gillard once of Bure Cottage, Horning, this was typical of the tact and sympathetic handling which made Dr Gordon as welcome in the cottages of the poor as in the mansions of the rich. In the combating of superstitious beliefs there are few country practices in which the doctor had to cast out an evil spirit. However even into the twentieth century he came across the occasional oddity such as a roasted mouse prepared as a preventative for whooping cough or the old superstition of stroking a dead man's hand for the treatment of a birth mark.

Doctor Gordon had a love of boats and had an intimate knowledge of the Broads. He became the first commodore of the Horning Town Sailing Club in 1910 and won many races with his boat ‘The Fox’ and later ‘The Vixen’. He also turned his hand to farming for both pleasure and profit. By the time he retired in 1918 one could say that in his time, he had been a doctor, a boat owner, a yachtsman, a motorist, a farmer, a politician, a local administrator and a magistrate.

His reputation, however within Ludham took a knock. Although he had a legal claim to the staithe, which had always had a mooring toll paid, it was said that he bribed an elderly wherry man to acknowledge this, much to the disgust of the locals who wanted it as a public staithe. He took the case to a London court and won. Obviously any opposition from the villagers was unlikely as travel to London was expensive. So this became a private dyke and Womack Staithe became the working staithe.

The staithe and Staithe House, Staithe Road

Ludham in the early twentieth century was a farming community, with local businesses providing essential services. There was plenty of competition with several pubs; an important millwright’s business and shops, all meeting the everyday needs of the village. There were other businesses too, builders, chimney sweeps, carpenters and many more on a small scale. A self contained place, but with the coming of the First World War, the pace of change was gathering.