Ruth Daniloff (nee

Dunn)

Memories of a Ludham Childhood

Memories of a Ludham Childhood

A miracle! I was a miracle. When my mother had lost all hope of having a baby, I appeared. My mother had suffered several miscarriages. When asked how many, she shrugged and said she couldn’t remember as if a miscarriage was something women had every day. She also gave birth to a little girl who weighed two pounds and lived for two days. My mother said the Chaplain in the hospital bullied her to have the baby baptized so she could be buried in Ludham churchyard with Christian rites. She named the baby Janet and often talked about her over the years. She claimed that she was reincarnated in my daughter, Miranda.

I think that my mother’s confrontations with the Chaplain in Cromer Hospital launched her disillusionment with organized religion, in particular with the Church of England.

Ruth's Mother, Molly Dunn as a child

My mother wanted to name me Ruth Miranda, but my father left Miranda off the registry and I became just plain Ruth. I disliked the name Ruth. The name was too Biblical. I wanted to be a Miranda like in the Hillaire Belloc’s poem my mother recited: “Do you remember an inn, Miranda? Do you remember an inn? And the fleas that tease in the High Pyrenees?" Over my mother’s objection, her older sister, Joyce, backed by Granny Chambers, organized my christening, as just plain Ruth, in St. Catherine’s church in Ludham. On the grounds she was ill, my mother didn’t go to the christening.

Over the next five and a half years my memories are bathed in mist like the marshes on a summer morning. My mother had purchased a small piece of land with money begrudgingly given to her by Granny Chambers who disapproved of my mother’s marriage to an out-of-work seaman who drank. There my parents built Dyke End, a small bungalow at the edge of a huge expanse of marsh. Dyke End was the last house at the end of a dirt road so muddy in winter that it was almost impassable. At the end of the road lay the marshes and across the marshes the river Thurne, which connected to a network of waterways known as the Norfolk Broads. In winter a strong northwest wind accompanied by a full moon and a high tide, could cause the North Sea to burst through the sand dunes and flood the marshes up to the edge of our land. Only a derelict windmill where swallows nested and cows sheltered from the rain broke the skyline.

In those days life seemed idyllic: collecting the milk at the nearby farm with my father, skipping over fresh cow pats in the lane. “Don’t get muck on your sandals,” my father’s voice; a farm horse on the other side of a dyke snorting softly through velvet nostrils; a mushroom glistening in the grass; a new-born foal rising on wobbly legs; a bull mounting a cow, and always things turning into other things: tadpoles into frogs, caterpillars into chrysalises, chrysalises into butterflies, blackberries into jam.

I always had animals. My favorites were a black and white collie called Barney and the ginger cat, Dandy. I dressed Dandy in dolls clothes and wheeled him around the garden in the pram. I included my two favorite hens in the pram until my father objected to the squawking. I owned caterpillars, tadpoles, frogs and a tortoise. I was heart broken when Ptolemy, the tortoise, disappeared. My father said it was because I had drawn pictures on his shell. I also raised numerous coloured mice, which smelled, up in my room. I kept rabbits in cages outside the house, feeding them on the cow parsley I collected from the hedgerows.

In those days I don’t recall anger or jealousy or the word “unfair” which would become my mantra. I don’t recall feeling a misfit. It was before Granny Chambers said I was an aggressive and unmanageable child. I felt at home on the marshes. I knew the dykes like the back of my hand. I loved the smell of dyke mud and the feel of water sloshing in my boots. I knew which dyke was covered with green slime, where you could find leaches. I knew which dyke was deep and which one you could wade across without the water slopping into the tops of your Wellington boots. I knew all the planks across the dykes, which ones were solid and which were rickety and submerged when you walked on them. I knew where to pick bulrushes and where the kingcups grew. I knew the names of wild flowers and I could read cow patties to learn the location of the cows on the marsh.

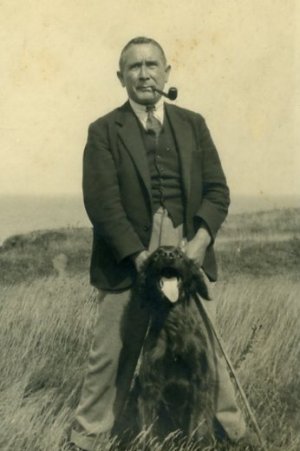

Ruth's Father, Raymond Dunn

The best mushrooms could be found on Charlie Green’s marsh at the far end of the track between the dykes leading to the river. I wondered why mushrooms sprouted on Charlie Green’s marsh and not on ours. My mother said it was unexplainable. A lot of unexplainable things existed on the marshes. Once my mother planted mushroom spoor on a load of manure in the garden shed. Raising mushrooms was one of her many money making efforts, like raising ducks, making gloves out of sheepskin, and selling her oil paintings. No mushrooms materialized.

As soon as the sky paled, I got up, and donned my Wellington boots. Usually my father was up, sitting on the veranda in his pajamas, smoking a cigarette and drinking his first cup of tea for the day. He had already taken tea to my mother. As I ran down the narrow path from our house to the dyke, I felt the reeds wet against my thighs. I jumped on the plank over the dyke making it bounce like a trampoline. Earlier in the spring I had sprawled on my stomach across the plank dangling a jam jar in the water for tadpoles.

I turned right onto the rutted marsh lane. The farm horses on the other side of the dyke to my left stamped their feet and snorted at my approach. I couldn’t see them because of the mist, but they always stood in the same place near the gate, flank to flank, the head of one horse resting on the haunches of the other. I noted that the blackberries on the bank of the dyke to my right were so heavy they trailed in the water, which meant that later in the afternoon my mother and I would put on Wellington boots and pick them. The dyke was deep. Finding a foothold in the mud was tricky.

I stopped at the gate to Charlie Green’s marsh, heart pounding, fearful that other pickers were there before me. I heard no sound of voices only the distant mooing of a cow. Dew covered the grass. After crawling under the gate, I examined a cow plop to see if the cows were out. I liked the cows, but I was always frightened of the bull if he was out with them. I saw my first mushroom hiding in the grass. I knelt down and picked it. I turned it over to examine the delicate pink gills for worms. Then I peeled off the skin and ate the mushroom. I loved raw mushrooms. I filled my basket quickly leaving the small mushrooms. Tomorrow I would return for them. Mushrooms sprouted so quickly, if I stayed up all night would I see them grow, I often wondered.

Sometimes my mother sat me on the back of her old bike, and we pedaled the two miles to Ludham village to visit Granny Chambers. Granny Chambers lived with my mother’s oldest sister, my aunt Joyce, in a bungalow on the Norwich road outside the village. My mother said my aunt Joyce was “a bit odd” whatever that meant. Granny Chambers usually stayed in her room, lying on her high bed with the curtains drawn. I don’t recall Granny Chambers ever speaking to me or smiling. On the rare times Granny Chambers got out of bed, she dressed in black. My mother said Granny Chambers had been in mourning for her husband Frank all her life. This struck me as strange because it was such a long time ago. Frank Chambers had died when my mother was nine years old. I had the feeling that something bothered my mother about Granny Chambers, some secret, and it was more than those ugly black clothes she wore.

Five years after I was born, my sister, Primrose arrived and I was thrown out of paradise. She turned out to be nothing like her name. She was dark, stocky and good-looking like my father. Primrose was such a mouthful so I began calling her Prinky. Prinky turned out to be everything I wasn’t. She had dark curly hair. My hair was straight. Her disposition was sunny. She made people happy, especially my father. She showed affection; slipping her hand into his when he inspected the potatoes he had grown. I was too resentful to be demonstrative. My mother said the reason Prinky followed me around like a little dog was because she loved me and I must be patient with her and not tease her so much. Once I locked her in the coal shed behind the garage where my father liked to pee. We had a toilet, but he didn’t like using it. My mother said it was because he had spent too much time at sea. Spending too much time at sea was an excuse for a number of things my father did.

Prinky, Raymond Dunn and Ruth

I will never know if tipping Prinky out of the baby carriage was an accident. I remember it like yesterday. The sun was shining and the marshes golden with buttercups. Prinky slept in the high Victorian carriage next to the water tub, which collected the rain off the roof. Prinky was only a few weeks old because Nurse Rouse was still with us. I recall releasing the brake, the carriage tipping and Prinky sliding forward. Nurse Rouse ran screaming from the house in her white starched uniform.

“You naughty, naughty girl!” she cried. Her anger terrified me. She was always so gentle.

Today, I recall this incident when I glimpse the soft head of a baby with its pulsating fontanel. Prinky’s head never touched the concrete, but it could have done so easily. I was terrified by what I could have done, and the violence, which lay within me. The recognition of my own aggression made the barbarism I encountered later in Russia and the Caucasus somewhat understandable, though no less terrifying.

Prinky’s birth in June 1941 was in the early part of the Second World War. Following the German invasion of Poland in 1939, England and France had declared war on Germany. Norfolk, along with the rest of England, awaited an invasion over the North Sea. If a coastal invasion of England was imminent I was oblivious. I am not sure if my oblivion was because my parents didn’t want to alarm us children or if they really believed, as the line in Rule Britannia goes, “Britons never, never, never will be slaves.”

My mother had shown me all the countries colored pink in the World Atlas. “All those countries are part of the Brtish Empire,” she said, running her fingers over the page. “They belong to us.” In my mind, England was the most important country in the world, and I was lucky to be English. I couldn’t imagine anyone conquering England, let alone any of those countries colored pink. They belonged to us.

My actual wartime memories were a series of happenings as dramatic as the bedtime stories my mother used to tell me. What I was told about the war and what really happened coalesced into an exciting drama edited by my mother. I heard about the Blitz and Buzz Bombs over London, which killed thousands of people, but I never connected the Blitz with people dying. The players were colorful, and their exploits quite as dangerous as the confrontations between Tom Kitten, Jemima Puddle Duck ,Mr. Fox and Mr. McGregor. The characters remain in my mind: Lord Baden-Powell, the one-legged Battle of Briton pilot who drank beer at one of the local Norfolk pubs; Lord Haw Haw, the German propagandist who cut in on the BBC news; Winston Churchill with his boozy voice and promises of blood sweat and tears, poor King George with his stutter, not forgetting, the Devil himself, Adolph Hitler. My father sang:

Heil Hitler, Ya, Ya Ya.

Oh, what a horrid little man you are!

With your hair all plast, and your little mustache.

Heil Hitler, Ya, Ya, Ya!”

In those years we had a ringside seat to the war because the German bombers used the River Thurne on the other side of the marshes to guide them on their bombing forays north. My father taught me to distinguish the slow drone of a German plane from the English “Spitfires” sent up to shoot them down.

Once a German pilot waved to me as he shot past our house almost at the level of our kitchen window. There he sat in the cockpit in his leather helmet, his hand raised in a salute to me.

“He went on to spray Ludham village with bullets,” my mother said.

“Why did he do that?” I asked.

“For the fun of it,” my mother said.

Then there was the German spy. That night my mother had turned off all the lights and opened the blackout curtains a crack. “That light is flashing again,” my mother called, looking over her shoulder at my father sitting in his chair by the fire. Over the marsh, I saw the light on the riverbank blink twice, then stop, then blink again.

My father rose reluctantly from his chair and came to the window.

“Go tell Colonel Taylor!” my mother shouted. Colonel Taylor headed up the local Home Guard, which consisted of a few men too old or too ill to fight. If the Germans invaded, the Home Guard was supposed to protect us.

“A big joke,” my mother said. I understood from things my mother said that my father spent a lot of time in the pub with Colonel Taylor. She often referred to Colonel Taylor as a “boozy old bugger.”

My father barely reacted. Nothing seemed to upset him. He returned to his chair, sat down, took out his tobacco pouch and started rolling a cigarette. My father must have informed Colonel Taylor because a few days later the blinking light stopped and my mother boasted to everyone how we had caught a German spy red-handed.

My mother’s weapon against the Germans was cod liver oil and a gelatinous orange juice liquid issued by the government. There was no way to avoid the cod liver oil, which she took more seriously than the government-issued steel table air raid shelter. She said the shelter took up too much room and threw it into the garden. Our gas masks remained in their boxes. She said the German would never use gas though how she knew that I didn’t know. My mother boasted about what she called: “Making Do”. She turned the worn out collars of my father’s shirts, and when the shirts became too ragged, she made underpants out of them for Prinky and me.

The highlight of the day was four in the afternoon when the German and Italian prisoners of war returned from the marshes after cleaning the dykes. I ran to the top of the drive and climbed on the gate to watch them march past with their guard. I didn’t like the look of the German prisoners who were dour compared to the Italians who laughed and waved. An Italian with flashing white teeth presented me a flower he had made out of plastic wire. Prinky and I gave him one of our white mice with instructions not to feed it cheese otherwise it would smell.

One afternoon a German prisoner, a heavy set man in grey prison overalls and a doughy face, dropped out of line and approached the gate to watch me learning to ride a new two-wheel bike. He signaled to my mother that he wanted to help. The next thing I remember he had grabbed the seat of my bike and was running behind me as I wobbled around the lawn. He said his name was Hubert. He must have told my mother that it was his birthday because the next day she presented him with a chocolate layer cake she had baked.

“Poor Sod!” she exclaimed. “He has a wife and two children back in Germany.” Baking a chocolate cake for a German struck me as strange. The Germans were supposed to be our enemies.

Around the year 1940 when the German planes were turning London into rubble and everyone awaited the German invasion of England over the North Sea, I asked my mother if my father would join up. From time to time I overheard my mother and father discussing this ship called Penola, a 25-ton, three-masted topsail schooner that carried a crew of 8 . The Penola was berthed in Scotland. Once fitted out the Penola would be looking for a captain.

“But Daddy is really too old for that,” my mother said. “After being blown up by the torpedo and thrown into the sea for 8 hours he was never the same. His nerves are bad.”

I could see that my father was old by his crinkly grey hair but I never really understood my father’s bad nerves, because nothing seemed to bother him like when a German incendiary bomb landed in our garden, setting fire to the old pigsty next to the lane. The whole sky lit up. My father refused to put it out. There is nothing to bomb but marsh,” he said

“Sailors don’t know how to function on land,” my mother said. “It is not that Daddy doesn’t love you. He just doesn’t know how to operate on land. He has all those ancestral memories, but he could bring a four-masted schooner around Cape Horn in a force 7 gale.”

The sea took the blame for my father’s shortcomings: that he drank; that he couldn’t find a job; that he peed behind the garage, that he planted the daffodil bulbs upside down.

All excuses! I thought. So why was he more patient with Prinky than with me? Planting the bulbs upside down! Even I knew how to plant bulbs. None of this talk about ancestral memories made sense to me.

When my mother wanted to illustrate the sea’s out-of-control behavior, she pointed to the picture of a three-masted schooner riding out a storm, which hung over the bookshelf in the living room. In the picture, huge waves crashed over the ship while sailors, waist deep in water, struggled for their lives. Other sailors clung to the rigging in an attempt to reef in the sails, which flapped like frenzied birds. I found it impossible to imagine the stocky man with the grey crinkly hair who sat across from me in the armchair, swinging in the topsails like the sailors in the picture.

I disliked the picture and I disliked the sea. The few times I went to the nearby beach, I refused to go in the water while my mother sat for ages on the sand gazing over the horizon. It all made me very impatient because I wanted to go home. I didn’t understand why she liked looking at the sea when she was always saying bad things about it, like the sea having a mind of its own Nothing could stop the sea – not the breakwaters, not the sand dunes, nor the grass planted to hold the sand. “You can’t argue with the sea,” my mother said. All the breakwaters, sea walls and sand dunes count for nothing.

All this talk about the sea frightened me. For land to lie below sea level like most of the Norfolk coast struck me as unnatural and very dangerous,

Generations of Dunns went to sea,” my mother explained. “If you had been a boy you would have gone to sea.”

I recalled thinking that going to sea might be more exciting than staying in Norfolk which was so flat and boring. Then I looked at that picture on the wall and thought about the Northeaster and the sea rushing over the marshes.

My father had gone to sea because that was what the Dunns did. He first went to sea as a nine-year-old apprentice on a sailing ship out of Liverpool. My great grandfather ran a smuggling operation between Lyme Regis in Dorset and Brittany, which my father’s sister, Bertha said brought shame to the Dunn family. The Dorset coast was known for wrecking so he probably indulged in that pastime too. My grandfather, Eugene Henri Dunn, seemed to have stayed on the right side of the law, though he was demoted for running a ship on the rocks. To my knowledge, my father never wrecked a ship, although the ship he commanded was rammed by another vessel off the coast of South America, and he was imprisoned until he proved he wasn’t to blame.

During the depression in shipping after the First World War my father was foolish enough to take out intention papers in Baltimore to become a U.S. citizen. Such disloyalty closed the doors of the Cunard Lines and cost him his British naval pension and career.

Not so long ago when I raised my right hand to become a U.S. citizen I thought of my father and wondered if I was being disloyal to England not that I ever had any great feeling of loyalty to England. Nonetheless, I still find it hard to think of the U.S. as my country, which often leaves me feeling rootless and an outsider. My children claim they suffer the same alienation and blame it on me.

Schooling.

My life changed the day my Aunt Joyce rode out of her drive onto the Norwich Yarmouth road outside Ludham and was hit by a truck and killed. No one seemed to understand why she had shot onto the road like that. She was usually so careful. I wondered if it had anything to do with Aunt Joyce being “a bit odd” as my mother said.

What really struck me as odd about Aunt Joyce being hit by the truck was that the gardener who worked for Granny Chambers saw the figure of Aunt Joyce in the rose arbor three days after her funeral at Ludham Church. Granny Chambers saw her too. My mother said seeing a ghost was perfectly normal when someone died suddenly.

My aunt’s accident launched my disastrous education. Large amounts of money, anxiety and tears were spent on it. In the end I had nothing to show for it but embarrassment and regret.

After Aunt Joyce was killed by the truck, my mother’s older sister, Aunt Marjory, arrived at Dyke End with her school teacher friend, Elizabeth, and two bad-tempered Pekinese dogs called Tikey and Candy. The reason for the visit was to decide Granny Chambers’s future, where would she live and with whom. Aunt Marjory reminded me of a man with straggly grey hair, cut very very short. I realized my mother didn’t like Marjory much either because she called her a “bulldozer.” For some reason my father was always laughing behind Elizabeth’s back. To my mind Elizabeth was so much nicer than Aunt Marjory because she wore lipstick.

The next person to arrive to help solve Granny Chambers’s future was Great Aunt Betty. Great Aunt Betty looked very old. My mother seemed to like her. She praised her all the time. Great Aunt Betty was what my mother called a “real educator.” Great Aunt Betty had borrowed money and started a school called Maltman’s Green, which soon gained the reputation as one of the best girls school’s in England. You paid a lot of money to go there. My mother said great Aunt Betty wanted the best for her pupils, which included walking on Persian rugs and dining off antique refectory tables. After my mother’s father died, Great Aunt Betty had wanted my mother to go to Maltman’s Green, but Aunt Marjory, who became head of the family, vetoed it. It seemed Aunt Marjory had no use for Great Aunt Betty’s ideas about schooling. Aunt Marjory and all those women friends of hers were something called “socialists.” my mother said. They thought women should run the world, and they wanted to destroy the British Empire and break down the class system. Aunt Marjory said Great Aunt Betty wasn’t Christian enough with all those Persian carpets when children were starving around the world.

The decision was eventually announced. Granny Chambers would move in with us at Dyke End. My mother said Granny Chambers had given us some money so my father didn’t have to join the Penola. He could stay at home and help with Prinky and Granny. As for me, Great Aunt Betty invited me to go to her school, Maltman’s Green, free of charge. I recall my terror, when my mother told me of Great Aunt Betty’s offer, but I don’t recall crying. Crying didn’t seem to be the way I handled setbacks. I made scenes and I raised a barrage of reasons why I should not be sent away to school. As I recall, my main objection related to the purple shorts required as uniform for the younger girls at Great Aunt Betty’s school. I never wore shorts. Once my mother had tried to make me wear a pair of grey flannel, boy’s shorts after she had replaced the fly buttons down the front with a red zip. I guess my dislike of shorts had to do with my behind. My mother said fussing about how you looked was silly because big behinds ran in the Chambers family.

“The shorts were boy’s shorts,” I countered, “they didn’t even have pleats in the front. If they force me to wear the shorts, I will wet them.”

My mother said my complaints were silly because I didn’t understand how hard it was for her to look after Prinky, Granny Chambers and Daddy. How lucky I would be to go to Maltman’s Green; how she had wanted to go to Maltlman’s Green herself. Maltman’s Green was not like the high school where Aunt Marjory was headmistress, which was so ordinary and boring. Great Aunt Betty hired the very best teachers. She believed that girls learned when they did things they liked doing. At Maltman’s Green, I would be able to paint and draw and make things out of clay; all the things I loved doing.

At Maltman's Green School, Great Aunt Betty worried all the time about one of the girls falling sick. Each morning Matron checked our temperatures. I never recall my mother taking Prinky’s and my temperature like that. That morning, Matron had removed the thermometer from under my arm, scrutinized it and declared I had a fever. She had to be mistaken, I thought because I felt fine. Then Matron dispatched me and the new girl to the sanatorium. The new girl said she felt fine too, but Matron made us undress and get into bed. Taking off my clothes a terrible feeling of being alone came over me. Ever since my mother had left me at Maltman’s Green I had had this feeling. Now all I wanted was to go home. The feeling of abandonment got so bad that I suggested to the new girl that we write to our parents and tell them that my Great Aunt Betty was mad, and that she had incarcerated us in the sanatorium when there was nothing wrong with us. I had guessed that my mother would read the letter and say it was another example of my naughtiness, but the parents of the new girl arrived at the school. Now Great Aunt Betty glared at me. “You have told a lot of lies. Your mother is coming to fetch you and take you home,” she said. “I can’t go home until Monday,” I said. “My laundry won’t be back.” I couldn’t think of anything else to say. Great Aunt Betty looked aghast. She did not reply.

The most memorable thing about my expulsion from Maltman’s Green was my Aunt Betty’s blue sheets. Great Aunt Betty lay on a huge bed between these blue sheets.. The curtains were drawn in her room. A lamp burned on the dresser. I stared at the sheets. I had never seen blue sheets before. She lay on her back, her grey hair, usually worn in a bun, straggled over the blue pillow. “You know why you are here?” she said, turning her head to glare at me. I nodded. I knew it had something to do with writing those letters. “You told lies,” she said. I knew telling lies was bad. My mother always told me that lying was one of the wickedest things you could do. Bribing a policeman was second to lying. Great Aunt Betty told me that as her great niece, I had caused her terrible embarrassment in the school. My lies were so shameful that the parents of the new girl drove to the school in their Rolls Royce to demand an explanation

A few days later my mother arrived at Maltman’s Green. It turned out that Miss Holland and the other teachers told her stories about the crazy things Great Aunt Betty was doing. How she got up later and later every day, then when she did get up she demanded oysters. Her statements were wild. She was rude to parents. She had insulted an important Labor peer, who wanted to send his daughter to the school, and then refused to apologize. She had appeared at school assemblies wearing two hats. The most shocking: she had persuaded the school doctor to give her morphine. She said she needed morphine to calm her nerves because the Germans had dropped a land mine on the school playing field. Everyone said Great Aunt Betty was such an embarrassment, especially on Parents’ Open Days when she never bothered to conceal the syringe, but left it in full view in a glass of water in the pantry. No one dared suggest retirement. Matlman’s Green was her school. Great Aunt Betty told my mother I showed no remorse. My remark about being unable to leave until Monday because of my laundry proved I was morally delinquent. To help my mother, Great Aunt Betty had made an appointment for me with a Harley Street psychiatrist. Harley Street was the most important street in London for doctors. My mother must have realized that Great Aunt Betty was no longer able to run the school and took me to the London zoo instead.

In the train on the way home my mother talked a lot. She said how sad it was I couldn’t go to Maltman’s Green because it had been such a wonderful school before Great Aunt Betty got too old. She explained that her father, my grandfather Frank Chambers, had tutored Great Aunt Betty so she could enter Cambridge University. He had also tutored Great Aunt Agatha who had a clubfoot, and his two daughters Aunt Joyce and Aunt Marjory. I recalled Great Aunt Agatha visiting us at Dyke End once. With her clubfoot she was like a dwarf and far more frightening that Aunt Marjory. She also had hair cut like a man. My mother said that Great Aunt Betty was her father’s favorite. “I think my father must have taken one look at those women and decided no one would ever marry them,” my mother said. “ They weren’t pretty and they didn’t have fortunes. He knew he had to get them educated, or he would be responsible for them. That’s why he tutored them all into Cambridge.” He didn’t bother about his two sons, my Uncles Reg and Jack and that led to a lot of terrible things.

My mother talked a lot about her father. She rarely talked about Granny Chambers other than to say she always wore black and she stayed in bed all day. Her father was brilliant because he could do so many things well like teaching mathematics, designing boats, painting watercolors of the marshes and helping start the Norfolk Broads Yacht Club. He even designed a boat, which sailed in a very important race called the Americas’ Cup. She said that if he hadn’t died of a heart attack when she was nine years old, her life would have been different.

My mother said it wasn’t surprising that her father had suffered a heart attack what with all those women on his hands and Uncle Jack’s disgrace and Aunt Joyce going batty. All of that just about broke his heart. Much year later, my mother told me about Uncle Jack’s disgrace and how my Aunt Joyce went batty and had to be brought home from Switzerland in handcuffs “Jack was my favorite,” my mother said, “He wanted to build boats, but my father said that was not a profession for a gentleman.”

Uncle Jack’s disgrace happened when my grandfather was head master of Lincoln Grammar School. It seemed Uncle Jack got a bar maid pregnant then tried to get rid of the baby. It was very shocking. After that Grandfather Chambers sent Jack to Australia with the Church.

I was glad to be going home. My mother didn’t seem to be angry with me. She usually took my side against schoolteachers and other people she considered “inferior.” I think what she meant by “inferior” was that the teachers were so dull that they couldn’t inspire anyone to learn. She told me that she herself had been to seven boarding schools. Only her Latin teacher had inspired her.

Back at Dyke End my mother began to teach me at home. I made a fuss about reading and arithmetic. I liked the drawing and painting though we didn’t have money to buy the best kind of poster paints I wanted. I always wanted something, which we couldn’t afford. I didn’t understand why we never had any money and why my father didn’t earn money like other fathers. One day after lunch when my mother was drying the dishes, she hand me a knife and told me to look on the top of the handle. “See where it says FIRTH STAINLESS,” she said. “Thomas Firth was your great grandfather and he discovered stainless steel.” She explained how one day he noticed a piece of steel on a slagheap, which wasn’t rusting. He and his brother John Firth examined it and found a way to make other pieces not rust. In time, they started a steel foundry and made lots and lots of money. Thomas Firth founded Sheffield University and was made Mayor of the city. “So why don’t we have any money?” I asked. “The Firths were frightened of fortune hunters like Luigi. They didn’t trust women so they tied all their money up into this complicated thing called a Trust.” My mother explained that Luigi was a dreadful Italian count, which couldn’t speak English, who married my mother’s cousin, and spent all her money. The trust was administered by what my mother called the “bloody lawyers” in Sheffield. She was always sending letters to the bloody lawyers, asking if it was possible to break the trust or borrow against it, but nothing much came out of it, and we never had any money.

A school existed in Ludham village, but my mother didn’t want to send me there because the local children spoke broad Norfolk, something she said Prinky and I must never speak though she did a very good imitation of it herself with her friend Ula. I did learn to speak Norfolk, but only for fun.

“If you wanted to be taken seriously, King’s English was the only way to speak.” She said. “That was how they speak on the radio.” The alternative to Ludham Village School was Potter Heigham Village School, located two miles away from Ludham village in the opposite direction.

My mother made a special arrangement with Miss Bond and Miss Wilson, the two maiden women who ran the school. They spoke “proper English.” Miss Bond and Miss Wilson said I could eat lunch with their adopted daughter Shirley. Like that I wouldn’t pick up a Norfolk accent or other bad habits.

The best part of going to Potter Heigham village school was the walk we took each morning with Prinky in the pushchair. Huge clumps of primroses, which I loved to pick, grew on the high banks on one side of the lane. On the other side of the lane was Ludham airfield. Through the barbed wire you could see the planes sitting on the runway.

I don’t know why my mother decided to take me away from Potter Heigham School after a year and send me to the boarding school for junior girls attached to Norwich High School. People told my mother it was a good school. Maybe my mother thought I wasn’t learning anything or she was fed up with my arguments. I argued a lot, especially for things I wanted. Outside our home I was too shy to talk let alone argue. Anyway, I never had anything to say. I don’t think my father liked the arguments I had with my mother. He just sat in his chair and said nothing, or talked to Prinky. Sometimes I thought my mother wanted to send me to go to the boarding school because of my arguing, which only made me argue more.

Stafford House, the boarding school attached to Norwich High School, was run by Mrs. Arnold a very frightening woman with grey hair pulled back in a bun and a strident voice. She never smiled. Each Sunday the girls walked in a crocodile line to church where the incense made me feel sick.

After church Mrs. Arnold invited the vicar for lunch. At night I couldn’t sleep. No sooner were the lights out in the dormitory than my feeling of aloneness overwhelmed me. I did everything I could to keep the other girls in the dorm talking so I wouldn’t be alone. As soon as they fell silent I had this feeling of panic. Supposing I never went to sleep again. Sometimes I stayed awake until the bell rang in the morning for breakfast.

All the time I kept thinking that my mother would take me away if she knew what a terrible person Mrs. Arnold was and how I couldn’t sleep, and how every Sunday evening she forced the girls into her drawing room to recite catechism. I knew my mother didn’t want me to be confirmed because we never went to church.

Even my father wouldn’t have liked Mrs. Arnold, I thought. My father had all these things he said about people he didn’t like. I bet my father would have called Mrs. Arnold “a whore in her heart and a bitch all round her belly.” That was one of his favorite sayings. My mother loved my father’s funny expressions and all the stories he told about being a sailor, like the ships cook being shoved into the oven because he burned the Christmas turkey, or the first mate falling into a vat of boiling oil.

Each morning we girls marched in twos across the main road from Stafford House to join the regular Third Form at the main school. I enjoyed learning to write, creating colored patterns with the letters. Most of the time, I plotted on how to open the door to the supply cupboard when the teacher wasn’t looking so I could steal the colored papers, exercise books and pens. Just looking at all those piles of colored paper I felt my heart race with excitement. I wanted to own them. Also I stole a blue fountain pen from the teacher, which I planned to give my mother, but then I slipped it back in the teacher’s desk because I knew my mother would ask where the pen came from. When I went home for the holidays, the arguments with my mother continued, mostly about being nice to Prinkie, or playing with Beryl the daughter of the farmer who lived next door. Beryl was a pretty big boned girl with curly blond hair and two horses. The more my mother criticized Beryl the more I wanted to be like her. Beryl had ponies and nice clothes. It was hard to know what bothered my mother about playing with local children. I don’t think my mother was a snob. It was the Norfolk accent. She didn’t want Prinkie and me to talk Norfolk.

My mother complained children who spoke with a Norfolk accent were common. Common was a word my mother used a lot. I was unclear exactly what it meant. It was not so much that Beryl was common, my mother said, but she tried not to be common. Trying not to be common was worse than being common. “She twists her vowels to hide her Norfolk accent.” My mother said. What was so strange was that, my mother admired Beryl’s father because he was what she called authentic. “He loved his farm and always had interesting things to say about it,” she said. My mother talked a lot about people having character. I could not see the difference between class and character because Beryl’s father walked around the house with cow manure caked on his Wellington boots. When he shaved, which wasn’t often, he shaved over a kitchen sink full of dishes. To my mind this was more shameful than some of the things my father did. Also Clifford Kittle refused to have indoor plumbing in the house and made everyone use an outhouse behind the lilac bushes in the garden, which Beryl really hated. At least, we had indoor plumbing even if my father went behind the garage sometimes. I felt like I didn’t belong anywhere. I wanted a father who worked like other fathers, who wasn’t 19 years older than my mother. I didn’t want a mother who used bad words like “bloody,” “bugger” and “sod” all the time. I wanted us to have money so I could have nice clothes like Beryl’s.I wanted to be like everyone else.

Looking back I realize that my mother’s anxiety about me having local playmates was an English class thing which created great loneliness for me growing up. When I was nine years old, I left Mrs. Arnold’s and graduated into the senior school. Each morning I made a 55-minute journey from Dyke End to Norwich on the bus. My father accompanied me to the bus stop and met me in the evening. When I was 11 years old and in my first year at the senior School, I won a prize: a book called “Friends of Fur and Feather.” I didn’t understand why I got a prize because I don’t remember being good at any subject. My favorite pastime was giggling with my friend, Judy Hurn. We didn’t laugh at anything. Nothing was funny, at least, not what you could explain. We just had to catch each other’s eye and we collapsed into uncontrollable of giggling: the kind of giggling you couldn’t stop however much you wanted to. I only felt happy when I was giggling. What are you laughing at? The teacher would ask. I had no idea and giggled more. Sometimes Judy and I giggled so hard the teacher would order us outside into the corridor or to the head mistress’s office. Sometimes the giggling got so bad, that I wet my pants. Judy seemed to have more control over her bladder because she didn’t leave a puddle under the desk as I did on several occasions. Not unexpectedly, my mother was summoned to the School. She said Judy Hurn was a bad influence and the teachers were uninspiring.

I remained at Norwich High School for almost four years, avoiding expulsion and learning the minimum. At home my mother and I continued to argue. She loved to argue. I think I did too. Our arguments went back and forth largely centered on the subject of how much I disliked Norfolk and England.

“Norfolk is cold, ugly and boring. Never, never would I live here,” I said. Sometimes I thought my mother used the arguments to educate me.“Artists loved to paint the Norfolk skies because water makes them luminescent,” she said. She loved Norfolk. “But there are no mountains in Norfolk,” I said.

At this time what interested me was everything American. I begged to be allowed to go into Norwich to see American movies. My mother didn’t even like me cycling into Ludham village in the hopes of seeing the American soldiers stationed at the nearby airfield: “So what’s so great about the Americans? “she said.

“The uniforms of American soldiers are better quality than those of the English soldiers,” I told her. My father snorted. “Americans are overfed, over sexed and over here,” he would say. He and my mother would laugh. I knew they said that to annoy me. Meanwhile, my mother continued to lecture me on the importance of education. Her messages were confusing. There was nothing worse than an ill-educated person, but for women education could be ruinous as it had been for her two sisters, Aunt Marjory and Aunt Joyce.

“Marjory became a lesbian with a lot of silly ideas about socialism and women running the world and Joyce had a nervous breakdown and spent her time chasing vicars and scout masters who were weak specimens,” my mother declared. “If I hadn’t walked out of Oxford, met Daddy and got married, I wouldn’t have had you and Prinky,” she liked to say.

Prinky never participated in these arguments. If they became too heated, she hid in the ditch behind the garage. From the way my mother talked, she took pride in walking out of Oxford after two years. I kept thinking that if she had finished her degree she could have become a schoolmistress like Aunt Marjory; that we would have money. She wouldn’t have had to undertake all the moneymaking schemes, which never panned out, the latest one being one hundred baby ducklings being raised in the decommissioned Nissen hut at the edge of the lawn. Maybe if we had money I could have had a pony like Beryl.

Once my mother revealed that when she was at Oxford she had written poetry and that the poet W.H Auden had asked her to contribute a poem to an anthology.

“So couldn’t you have just stuck it out at Oxford?” I asked her.

She shook her head. “I just couldn’t,” she said. “If I hadn’t walked out I wouldn’t have met Daddy and had you and Prinky.”

The “just couldn’t,” answer never failed to upset me. I didn’t know what to say. So you shouldn’t have had us? So she had given up everything to have us? It was not my fault that I was born. If not for us, she might have written poetry. It would be many years before I discovered the real answer as to why she walked out of Oxford.

When I was 14 years old, my education took another turn, thanks to a boy with flaming red hair called Jolyon Byerley who lived with his family across the marsh from Dyke End. By that time, the war was over and the boat yards were in business again. My mother’s best friend, Joylon’s mother, Cis, lived in one of the small bungalows on the riverbank. My mother didn’t have many friends because she considered most people dull, but she tramped across the marshes in all weather to visit Cis because Cis made her laugh Cis was a small woman, a one-time music hall actress, who called everyone “darling”. Her hair must have been red like her sons, but now she wore it in a yellowing coil around her head. While Cis chain-smoked, her husband, a retired British army major, marched up and down the river bank with a megaphone shouting for the motor boats to slow down before their wash broke down the banks.

Jolyon talked and dreamed boats. I had a crush on Jolyon, but was so shy I couldn’t even talk to him. He was so self-confident. If I stood at the living room window at Dyke End and looked across the marsh, I could see when he raised the sail of his boat. If the wind was in the right direction I tore down the marsh path so I could reach the river in time to see him pass. Then, not knowing what to say to him, I hid in the reeds.

Cis said that as soon as they had money for the fees, Jolyon would return to his boarding school in Scotland. Jolyon had nothing but good thing to say about this school called Kilquanity House. He spoke highly of the head master John Aitkenhead, who was a conscious objector during the war. He described Kilquanity as one of those progressive hearts-not-heads sort of places where pupils called teachers by their first names and didn’t wear uniforms. The pupils made the rules at weekly meetings. If you preferred to ride your bike outside instead of going to math, you did that. I liked the sound of it.

My mother listened to everything Jolyon said about Kilquanity and a few weeks later we were on a train to Scotland to visit the school. From the train window I saw hills and winding roads flanked by neat stonewalls and everywhere sheep, not like Norfolk, which was so flat with nothing but cows.

John Aitkenhead, the head master of Kilquanity, met us on the platform at Castle Douglas station wearing a kilt. Much of what he said I didn’t understand because of his accent and the different words he used like “aye” for yes and “wee” for small. Surprisingly my mother, who usually made such a fuss about accents, didn’t even comment on this.

I could see from the way John Aitkenhead and my mother talked that they saw eye to eye on education. When we returned home, my mother wrote to the “bloody lawyers” asking for money for me to go to Kilquanity, but they refused. To raise money she sold Grandfather Chamber’s antique tallboy, which stood in the corner of our living room. We packed my father’s wicker trunk, which he had used to travel the world. So began my four years at Kilquanity House School, a co-educational school of 30 students, which was located in Galway on the West coast of Scotland.

It took me a while to adjust. As the only English student, I was a Sassenach, which is what the Scots called the English. Each time I opened my mouth I felt self-conscious because of my accent. I didn’t like math or chemistry so I didn’t go to those lessons. I liked English and Latin because John Aitkenhead taught them. John liked my essays and encouraged me to write more. After the once-a-week meetings we learned Scottish country dancing taught by a very fat woman who was so light on her feet she floated.

The kids rotated jobs around the school. One of my chores was working in the kitchen, a cavernous room in the basement of the house with a wooden table and flagstones on the floor. Michael Grieve, a stocky young man, who wore a heavy white apron over his kilt, was the cook. Michael didn’t seem to hold my being a Sassenach against me and taught me how to make fudge with my ration of brown sugar. Michael was the son of Hugh MacDiarmid, the famous Scottish poet, the father of Scottish nationalism and a communist. As I peeled the potatoes for that night’s dinner Michael told me about all the wonderful things the Russians were doing to make everyone equal. The idea of everyone being equal appealed to me. Michael also set me straight on how the English had oppressed the Scots throughout history. For the first time I felt ashamed of being English. “One day the sacred Stone of Scone will leave Westminster Abbey and return to Scotland where once again it would crown the kings of Scotland,” he said.

I was too shy to argue, but that didn’t seem to worry Michael who loved to talk. I loved his stories of the Scottish heroes like Robert Bruce and William Wallace who had put one over on the English. If only I belonged to a Scottish clan, I thought, and could wear a kilt. My friend Marylyn, who was Scottish, said the English couldn’t wear kilts. Girls couldn’t wear kilts either because of their shape. Ten yards of pleating around their hips made them look fat.

When I was 15 years old and home from school for the summer holidays, my mother told me about the growth on my father’s lung. We were on our way down the path to the compost heap with the buckets of household scraps for the chickens. I heard the clank of my foot striking the cover over the drain. The world as I knew it shifted. My mother described the “burning out” of the growth which would take place at the hospital in Norwich. When I was home from school I saw my father’s “burning out,” though the opening of the top buttons of his pajamas. I saw the raw flesh, the skin peeling from his chest in strips far worse than mine when I spent too much time in the sun.

My father never complained. He had a strange attitude towards health. I never recall him suffering minor headaches or indigestion like my mother. He had certain chronic conditions, such as a smashed up hand, bouts of typhoid, the near drowning, a bad eye around which he built stories to make people laugh. He boasted that he didn’t hold with overcoats and had never worn one in this life. He tried to treat the growth as an inconvenience. He said that when summer came he would be fine. But summer came and he wasn’t fine.

After my mother died I found her description of my father’s death in the bottom drawer of her desk. She treated it as though he were Sir Richard Grenville fighting the Spanish Armada on the decks of the Revenge.

“The ship had come through the narrows. But it was all bluff.” She wrote “Then the game began in earnest. The enemy had breached a great hole in his defenses and everything poured in on him at once.”

At the Norfok and Norwich hospital they gave him twice the usual dose of radiation because he joked with the nurses and never complained. Then he came home.

“It was not a shoddy compromise, but a hell for leather rattle of sword play as passionate an adventure as he ever undertook”, she wrote. “The man who had been to sea for a living, knew what living meant. He knew that dying came in to it. It was not man against man, but man against the wind and the sea, man having a bet with God. Thus he rode out the tremendous sea of his disease. Cancer. The word has a heavy ominous sound. He treated it with courtesy, almost as one might treat an unwanted guest, and then in the end he disposed of it by the supreme act of dying. The host has slipped away and you can hear the sound of his laughter in the rafters.”

My father’s death gave my mother another opportunity to attack the local vicar . My father’ coffin was supposed to lie in the church at Ludham until the burial but it was Easter and the vicar said no dead bodies in the church because his parishioners wouldn’t like it.” My mother was incensed. “Easter is just the time for dead bodies in a church,” she said, “My husband would prefer to spend the night in his garage than in your church,’”

Reading this account of my father’s last days, I shed the tears I failed to shed earlier. “A few hours before he died, my father told my mother that a procession was passing through his room and he was part of that procession.

I often wondered if my father’s procession was full of all those ancestral memories, my mother talked about. Sometimes I fear they have become attached to me. Some people read about the sexual shenanigans of celebrities at the supermarket check out. I find myself reading about disasters at sea, about tidal waves, tsunamis, hurricanes, typhoons, sharks, piracy and the Bermuda Triangle.

I often wondered why my mother had married my father. Daddy made me laugh,” she said. That was something she needed after her Oxford debacle. There was ridiculousness about my father’s sea stories, which also appealed to me. He repeated them so many times I almost knew them by heart:

“Grab him by the balls, Sir!”

The Trotsky arrest was my mother’s favorite story, following the Trotsky story was my father’s proposal to a female missionary in Aden only to be told she was married to God. In the Trotsky story, Trotsky was on his way to join Lenin in Russia when the British Naval Command ordered my father to remove him from this ship off Halifax. As my father told it, hysterical women who wanted to accompany him surrounded Trotsky. Trotsky hid under the heavy boardroom table and refused to leave without the women. My father was dressed in full dress uniform, his only weapon being his sword. That was when the little midshipman who accompanied my father yelled: “Grab him by the balls, Sir!”

Trotsky wrote in his biography of being manhandled by a brutal British naval officer. Many years later I told this story to a Russian friend, who asked why my father hadn’t squeezed Trotsky a lot harder.

My favorite stories were mysteries at sea like the Marie Celeste a 100-foot barquentine with a crew of 7 found abandoned on December 13, 1872. So what happened to the crew? I asked my father who didn’t seem that interested in the crews of ships disappearing into thin air. I preferred mystery type tales to his stories of falling down the hold of a ship or the first mate tumbling into a vat of boiling oil He shrugged in response and said anything could happen at sea.

One afternoon after tea, my mother opened the drawer of her desk and removed a picture of my father, along with his Extra Master’s certificate in sail dated 1908, his intention papers to become a U.S. citizen, and some medals my grandfather won in South America. In the photo my father’s hair is black. He is wearing full dress uniform of Lieutenant Commander of the Royal Navy with gold epaulets and braid. His right hand cased in white gloves rested on the hilt of his sword.

“Your father was a fine figure of a man,” my mother said replacing the photo in the drawer.

It would be many years later, when I encountered the broken young Russian soldiers from the war in Chechnya, that I understood what war does to fine figures of men.

During my three years at Kilquanity, I absorbed a lot of useless information like the names of the battles where the Scots routed the English. I learned to love bagpipes, dance the eightsome reel, milk a cow, recite poems by Robert Burns and eat a minced up concoction of sheep’s innards called Haggis. John Aitkenhead and most of the pupils at Kilquanity were Scottish nationalists. Scotland was my introduction to the insatiable desire of people to possess freedom and independence.

Age 18 I left Kilquanity without any ideas in my head as to what I wanted to do with my life. Life wasn’t something I wasn’t ready for. I was dissatisfied with everything and I was incapable of making a decision about anything. If I had any real interests, it was clothes and boys. Despite all her negative comments about uneducated people, my mother did nothing to encourage me to get more education. I had spent too much time riding on my bike around the hills near Castle Douglas so I hadn’t passed all the required school leaving certificates to allow me to enter a college. Furthermore, I think my mother really believed education was bad for you. She was always giving me examples of how education could drive you crazy.

“Joyce got into Cambridge where she spent all her time chasing vicars and scout master,” she said. “Joyce was very clever, but she had some sort of mental breakdown. They sent her to Switzerland to recover but it was so bad she had to be brought back to England in handcuffs.”

The worst victim of the educational fiasco in our family, according to my mother, was mother’s cousin Noel. Noel’s father, Great Uncle Charlie was so brilliant he had driven both his wife and his son crazy. He was knighted for knowing everything there was to know about Oliver Cromwell. My mother felt sorry for Noel. “Noel was very nice and brilliant. He now now lives at the YMCA wanders around Oxford in his slippers. The only thing he knows is the football scores,”

I found all of this going crazy very puzzling. I often imagined Noel shuffling around Oxford in his slippers and wondered what Great Uncle Charlie had done that Noel didn’t have any shoes.

I knew I wanted to travel. I wanted to meet foreigners. I felt more at ease around foreigners. Around foreigners I never felt judged. I felt English people judged me because I didn’t have the right accent or used the wrong word which would immediately reveal me as lower class. Then I had this strange family, with a mother who talked to ghosts and wrote poems, which no one ever published.

As always we were short of money, so my mother said I should get a job. A job is what you get before you snag a husband. I wasn’t enthusiastic about either a job or husband. Following a three-month secretarial course in Norwich, which I failed, I took a job at the Norwich school for the Blind taking dictation from a veteran who had been blinded in the first War. My mother suggested the Women’s Royal Navy, but that didn’t appeal either. Then my mother found this advertisement in the Lady Magazine. A woman psychiatrist by the name of Dr. De Seret, working in a clinic in Switzerland was looking for an au pair girl for her two children age six and eight. We filled out the application. I was enthusiastic.

The clinic was housed in an old converted castle in the village of Chavorney not far from Lausanne. About all I remember about Dr. de Seret was her enviable French elegance, and the perfume she wore called Fleur de Rocaille. She lived with a former racing driver who had lost his arm in a driving accident. We had special keys to move around the building so the patients who suffered what was referred to as “nervous disorders" “couldn’t escape.”

When I wasn’t looking after the two children I spend my spare time with Pierre, the grandson of the owner of the clinic. They were Swiss German. He was in his fourth years at medical school. I loved Pierre’s attention, though I don’t think I loved Pierre. He helped me with my French, taught me skiing and took me for trips into the mountains on his scooter. Pierre and I spent so much time together that I think his parents thought that when he had finished his medical school we would get married. His mother gave me a beautiful blue and silver coffee set which I have to this day. Somehow I just couldn’t imagine myself as the wife of a German Swiss doctor.

While I was in Switzerland, my mother sold Dyke End and moved to Oxford where she purchased an ugly little row house with 5 years left on the lease. I never understood why she moved to Oxford when she had always been so unhappy there. She said it was for Prinky’s education or maybe she hoped to find good husbands for her daughters.

My mother couldn’t stay away from Norfolk for long. She left Prinky to run the Oxford House by renting out student rooms and returned to her beloved marshes. There she purchased a small caravan, which she parked behind a clump of bushes in the garden of an interpedently wealthy fruit farmer in Ludham .He had a wife and two boys’ and according to my mother was a natural healer. She said that anyone could learn to be a natural healer. I suspect my mother was in love with the fruit farmer because she was always talking about him. The two of them spent time at the Norwich spiritualist Church with a medium by the name of Mrs. Duffield.

When I left Switzerland and returned to England, Pierre accompanied me and took up an internship at the Oxford hospital. When it was time for him to return to Switzerland, we broke up. I don’t recall who broke up with whom and why. Whichever, I was devastated. An Italian friend by the name of Gabriella suggested I go to Rome and stay in their family’s apartment while they were on vacation. For the first several weeks in Rome I was miserable staying by myself in the dark apartment writing tearful letters to Pierre and plotting how to get him back. Then I met Paolo. Men like Paolo are why the English, especially the English women make fools of themselves. The men are too good looking for their own good and that included Paolo. He laughed a lot, displaying beautiful white teeth, which glittered in the sun. He liked to sprawl his beautiful body on the beach, sit at cafes drinking strong coffee and listen to his friends singing. He loved life, something I knew nothing about. He was fun. I needed fun. I loved walking at the side of such a gorgeous man.

I must have written enthusiastically to my mother about Paolo because when I returned to England, she questioned me. Was I thinking about marrying him? Didn’t I know Italians were Catholics? They didn’t believe in divorce.” My mother had even less use for Catholics that she had for the Church of England.

She needn’t have worried about Paolo. In December when Palo visited me in England the rain soon washed off the Italian patina. I even found his beautifully cut Italian suits and shoes with the pointed toes ridiculous when splashed by mud. Needless to say I was depressed when Paolo returned to Italy and I was left in the hateful English Weather.

LUTHANY COTTAGE

Another of my mother’s crazy ideas, I thought when I learned about her plan to sell her caravan, (which she kept at friend’s house in Ludham) and buy a 15th century cottage scheduled for demolition in Hoveton St. John. My mother had no money, but she offered her usual reassurance: if something felt right, money would be found for it. She rarely thought things through.

Prinkie and I had given her an old van when her arthritis made movement more difficult, otherwise she lived on her old age pension or on the occasional financial dribbles from the Firth Trust. We argued that even if she could afford to restore the cottage it would never be hers because it belonged to a local landlord who refused to sell any of his estate which he claimed his family had acquired when they came over with William the Conqueror in 1066. The landlord was just the sort of person who made me want to leave England. He resembled an over-bred blood hound and talked as if he had a plum in his mouth. He reminded me of those hundreds of Americans who claim to have come over in the Mayflower.

I recall the first time my mother took me to see the cottage. At this time I had a job in Oxford doing secretarial work for a firm of Antique book dealers. We parked the old van on the grass verge off the Horning Road. The cottage stood some 200 yards from the road surrounded on all sides by fields of sugar beet and nettles. Sparrows flew in and out of holes in the thatch. I followed my mother through the long grass to the door, which hung on one hinge. She stopped and pointed to a mangled shrub under the window. “That’s a fig tree,” she said. “A fig tree says the cottage was once part of the church.” My mother was big into Church history and, as child, she had dragged me around the countryside to teach me the difference between a Saxon church tower and a Norman one. Meanwhile, she never lost an opportunity to make fun of vicars.

Inside, the cottage smelled of molding thatch and dead creatures who had died in the eaves. Wall paper fell in sodden strips from crumbling plaster held up by heavy oak beams. The second floor had collapsed. We mounted stairs one rotten tread at a time to the third floor attic. My mother wanted to show me the priest’s hole under the eaves.

“The Pope refused to let Henry the Eighth divorce his wives, so Henry destroyed all the monasteries. The monks had to hide,” my mother explained, as she urged me to crawl into the dark hole under the eaves. I refused. A carpet of bird droppings covered the flooring.

Outraged, at the thought of the cottage going up in flames, my mother had invited a representative from the British Historical Society for an inspection. My mother’s argument about the priest’s hole and the fig tree must have convinced the inspector that the cottage had historical value because he lifted the demolition order.

The landlord tried to disguise his anger, but in the end he gave my mother a lifetime lease on the cottage. After she died it would go back to sugar beet. She applied for a grant from the Norfolk County Council and, like most grants, this one came with conditions. All thatch had to be stripped from the rafters and replaced. “Regulations be damned!” my mother wrote in one of the periodic articles she wrote the The Eastern Daily Press. “To remove the thatch from the rafters would be like asking a Victorian lady to strip in public.

She decided to name the cottage “Luthany” after a poem by the English poet, Francis Thompson. She quoted one line “With thee take, only what none else would keep” I looked up the poem, only to find it incomprehensible and that the poet had been an opium addict who had lived on the streets. It would be many years before I would re-read the poem.

My mother didn’t worry that everyone said, Luthany was an impossible undertaking. She said everyone who had ever lived in the house (and their ghosts) would help her. I tried to imagine all the individuals who had lived in the house over the last 400 years without success. I am still waiting for the day when day some technological genius devises a method of recording everything which has ever happened in a place like a television program.

For my mother the cottage was love at first sight, the kind of love a woman has for a messed-up man; a challenge to straighten him out.

“The rafters themselves were the lords and masters of that magnificent house of mine,” she wrote. “They were tree trunks and purloined ship timbers, lashed into place with ropes and pinned with great wedges. They were twice the size one would expect and leaned affectionately against the giant chimney breast as though daring anyone one to enforce the demolition order, the one impregnable part of a virtual wreck.”

I wondered if my mother’s love of Luthany was the kind of love she had for my father. She had nursed him through cancer until he died. Now another ruin confronted her. Her pride in overcoming adversity was so great, that I sometimes wondered if she didn’t purposely create adversity to overcome it. Later, I asked myself if I wasn’t a risk taker too. There is something exciting about undertaking the impossible.

My mother did most of the work herself. Carting the rubble from the seven foot fireplaces, mixing lime and cement in a bucket, and slopping it on the walls. The unevenness didn’t matter. Unevenness was character. Not one right angle, or one symmetrical door existed in the house. Neither Prinky or I or anyone else gave her the encouragement or inspiration she deserved. It makes me ashamed to think about that now. There was something magical about what she had done, and I found myself admiring her spirit. Who else but my crazy mother would undertake such a project.

She had furnished the cottage with furniture belonging to my grandfather and with pieces she had picked out of junk stores and finished herself. Over the huge Elizabethan fireplaces she hung horse brasses. She said she wanted Luthany to be a place where Prinky and I could bring our children.

Despite the presence of these benign spirits who had supposedly helped my mother, I always felt uneasy in Luthany. My mother said the place was full of spirits though she never actually stopped mid-sentence and said “there’s a ghost standing behind you.”

“So how do you know?” Her certainty irritated me. “I just know the ghosts are there,” she would reply. “But you don’t have to worry, they’re all friendly.”

I worried. How could the ghosts possibly be benign, considering the blood spilled over the Norfolk landscape. The boots of Romans, Saxons, Vikings and Normans had trampled the marshes, not to mention the violence in the attic when the King’s men dragged a monk from his hideaway. Only three years ago, as the sea receded on the beach a few miles up the coast, archeologists had identified the footprints of three hominids: two adults and a child, proof that millions years ago hominids on their way out of Africa had made a stop off in Norfolk.

I slept badly at Luthany. If a ghost materialized I did not want to see it, so I closed my eyes, pulled the covers over my face and tried to block out the sound of small animals scampering across the thatch in the eaves. The old ship timbers creaked as if riding out past storms.

“So did you see any ghosts last night?” My mother would joke when I came down to breakfast. That’s when the augments began. “There is more in heaven and earth that is dreamed of in your philosophy, she would say. This quote from Hamlet infuriated me. My conversation with my mother consisted mainly of arguments. No one has proved that ghosts exist,” I said. “No one had produced a convincing photograph of a ghost.”

“So why have so many people seen them?” she said, listing all the people she knew who had seen ghosts. “Granny saw Joyce standing at the end of her bed the day after Joyce rode out of the driveway and was run over by a truck. The gardener saw Joyce standing by the arbor in the garden, Ula had seen had seen Father Jeremy.

My mother’s close friend, Ula, and her husband lived in Ludham Hall which stood two miles across the marsh from St. Benet’s Abbey. Today all that remains of St. Benet’s, once the largest monastery in the area, are a few flint arches where cows shelter from rain. Supposedly an underground passage ran from the Hall to the Abbey. As Ula told it, one night she woke to see a cowled figure standing at the end of her bed. “Who are you?” she asked. “Father Jeremy,” came the reply. “Pray for me!”

Then my mother quoted people who believed in ghosts, but hadn’t actually seen them. Like Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and William James.

The issue of ghosts came to head one weekend when I was visiting my mother and she told me about Fairarch. She said Fairarch was a monk who had once lived on the Island of Iona. She talked to him regularly. This information shook me. So my mother was talking to some nonexistent person in her head: wasn’t this what mentally ill people did or for which psychiatrists sent you to the funny farm? The church called it possession and trained special priests in how to exorcise the demons. This scared me . My mother referred to the work of Carl Gustave Jung. She was always taking books on Jung out of the library. She said she like Jung better than Freud, because Freud said everything had to do with sex. Jung, on the other hand, talked about two memories. “We have two memories she said: what happens to us in our lives, and what happens to us as a member of the human species.” None of this made sense to me and I attributed to another of her crazy theories along with her faith in spirits.

My mother didn’t seem to be crazy, though she might had inherited whatever mental thing which had afflicted my aunt Joyce. Did it run in our family? I never felt there was anything evil about my mother. Just embarrassing.

A brief embarrassing period was when my mother frequented the Spiritualist church in Norwich. One weekend when I visited her, she invited me to go to the church to hear a Mrs. Duffield, who was reputed to be the most famous medium in Norfolk. We entered a dark room on the second floor of a Victorian House on a side street in Norwich. Shapeless middle age women in dowdy clothes filled the chairs, so we stood to the side against the wall. Mrs. Duffield, a heavyset woman with a pasty face, stood on the platform at the end of the room. Her eyes were closed and incoherent words tumbled from her mouth. Her voice rose and she lapsed into English with a broad Norfolk accent. She announced she was receiving communications from the “other side.” People came forward in turn to take her hand and receive messages from the dead. A knot of fear settled in my stomach.

“I see a woman with very short hair,” Mrs. Duffield said when it was my mother’s turn to receive a message. “She says she loves you.” My mother’s sister, Aunt Marjory flashed into my mind. Bad blood existed between Marjory and my mother. After she died, Marjory left an antique Georgian ring that belonged to my grandmother and some Chippendale chairs which were part of my grandfather’s antique collection, to her lesbian friend Elizabeth. My mother never forgave her. Whenever I became aggressive my mother would say: “You are just like Marjory.” Being compared to Marjory never failed to upset me, especially after my mother said it was a relief when Marjory died of a stroke.

My turn. I wanted to leave. Mrs. Duffield took my hand. Her eyes were closed. “I see mountains,” she intoned. Switzerland, I thought, maybe Pierre would come back to me. “I see you near some pink blossoms. I see a rope with knots,” she said. The almond tree in our childhood garden, I thought. In the spring it was a mass of pink. My father had rigged up a swing in the tree. The rope broke several times and was very knotted. I didn’t know what to make of the image. I still don’t.

My mother soon became fed up with people’s unquestioning faith in Mrs. Duffield. Perhaps because of her low class Norfolk accent. Faith smacked of the Church of England, an institution my mother held in contempt. “I prefer to stick with Fairarch,” she said. Strangely there would come a time when I would be thankful for Fairarch and wished I could have a conversation with him.

The other embarrassment was the Ouija board:

One particular Ouija session remains in my mind. It was a freezing winter day. I shivered and zipped my ski jacket. Logs burned in the fireplace, but the room felt cold because most of the heat from the fire disappeared up the huge Elizabethan chimney. Centuries of soot build-up gave the room a musty smell. My mother wore the padded vest I had given her. Prinky was dressed in several sweaters. England was always cold and damp, especially on the East coast where the marshes offered little break from the gales blowing off the North Sea.

My mother cut a large circle from a piece of cardboard and placed it on the oak table in front of the fire. Then she took a ballpoint pen and wrote the letters of the alphabet around the circle. At the top she wrote the word YES; at the bottom, NO. When she had finished writing, she took a shot glass and laid it upside down on the cardboard circle.

Prinky and I drew our chairs to the table and closer to the fire. My main fear was that someone should look through the window and see us. At the sound of footsteps on the gravel outside we would grab the board and stuff it back in the drawer of the old oak chest.

I think the only reason we agreed to do it that day was because Prinky and I had boyfriend troubles, at least that is what we told ourselves. Prinky wanted to know if a monosyllabic architectural student loved her, and I wanted to know if Pierre would return to me. The three of us placed our index finger on the glass. The glass gave a start, and then darted towards the letters, like a horse out of the gate, to answer our questions. Fairarch always referred to our would-be boyfriends as “Lovely John” and “Lovely Pierre.” Yes, “Lovely John” and “Lovely Pierre” loved us. Would we marry them? The glass stalled.

We accused our mother of pushing the glass. She denied it.

Prinky and I rejected the theory that our mother pushed the glass deliberately. She was always talking about honesty and the importance of truth. Telling a lie was a serious sin in our household. So what was making the glass move? Maybe she was an unconscious pusher. Maybe Fairarch was the figment of a rich imagination, or a mind which had spent too many years alone. We conducted experiments. We tried to do Fairarch together, but without our mother. The glass jerked, stalled and refused to advance. As soon as my mother added her finger it shot across the board. On the other hand, my mother couldn’t move the glass by herself.

Now that Fairarch had entered her life, she said, she had no reason to do the Ouija.

My mother revealed she was writing Fairarch’s life. “How do you know about his life?” I said. “It comes to me in my head,” she said.

After my mother died, I found Fairarch’s life story stuffed into the bottom drawer of her bureau with a number of other writings and poems.

Looking back, I realize that much of my life I had been searching for an explanation of what moved that glass around on the Ouija board. Had my mother really lost touch with reality or did some power exist out there, which I didn’t understand? Religion offered no answers. I could no more believe in the Virgin birth or the Ascension than I could believe in Fairarch. If the Virgin had really ascended to heaven, she would still be in the galaxy according to the speed of light. I began seeking out articles on psychology and things relating to the brain. Understanding the behavior of the brain might offer some insight into the behavior of the shot glass or of my mother, I told myself.

Notes from the Ludham Archive researchers on this section:

Despite the threat of demolition, Luthany is still standing.

"Ula" mentioned above is Ula Pegatha Wright (born Ula Dashwood-Howard)

NICK DANILOFF

Ruth married Nick Daniloff. This led her to a life of adventure culminating in being expelled from the Soviet Union and meeting President Ronald Reagan. Here is how it happened:

When people asked Nick how we met, he always says that he had picked me up in a train: It was the last train from Paddington Station in London to Oxford, nicknamed the “The Flying Fornicator” by students. He claims he was looking for the prettiest girl on the train. I never thought of myself as pretty. He said I had red hair. That wasn’t true either. My hair was mousy brown and if I didn’t wash it every day it hung in greasy strands.

My version of the story is different. In truth, I had done the picking up. I had walked down the corridor of the empty train and noticed this young man in one of the empty carriages with his head in the London Times, I sat myself in the empty carriage on the seat opposite to him. He asked if I would like to read the paper. When he started talking I noticed he spoke with an American accent. This was a plus. He told me he was born in Paris, that he was studying politics and economics at Oxford, and he had a great grandfather who was a famous Russian general. He said he wanted to be a journalist and go to Russia. He was exotic, I liked exotic. I loved the idea of Russia and of his grandfather who fought for the Tsar.

As it turned out I was on the train with the man I would end up marrying. This man promised adventure.